You might think you have a heavy course load. Imagine being the instructor of record for approximately 5,000 students in a semester. In this episode, Dr. Kristina Mitchell, a faculty member and director of the online education program for the Political Science Department at Texas Tech, joins us again to discuss the design, organization, and management of high-enrollment online introductory political science courses.

Show Notes

- Mitchell, Kristina M.W., and Robert Posteraro, MD. “Making Arrangements: Best Practice for Organizing Tools in Online Courses.” (manuscript)

- Mitchell, Kristina M.W., and Whitney Ross Manzo (2018). “The Purpose & Perception of Learning Objectives.” Journal of Political Science Education (forthcoming)

- Quality Enhancement Plan (QEP) at Texas Tech University

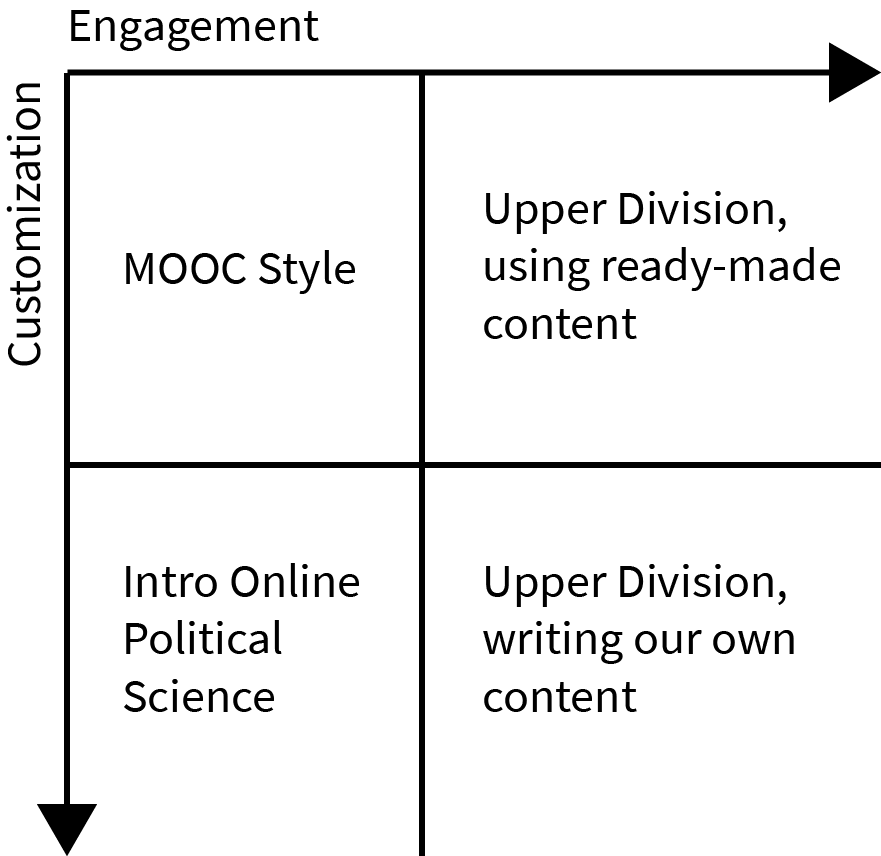

- 2×2 Course Development Matrix

Transcript

John: You might think you have a heavy course load. Imagine being the instructor of record for approximately 5,000 students in a semester . In today’s episode, we’ll focus on one extreme teaching scenario.

Thanks for joining us for Tea for Teaching, an informal discussion of innovative and effective practices in teaching and learning.

Rebecca: This podcast series is hosted by John Kane, an economist…

John: …and Rebecca Mushtare, a graphic designer.

Rebecca: Together we run the Center for Excellence in Learning and Teaching at the State University of New York at Oswego.

John: Our guest today is Kristina Mitchell, a faculty member and director of the online education program for the Political Science Department at Texas Tech. At Texas Tech, she is the instructor of record for over five thousand students each semester. Welcome back, Kristina.

Kristina: Thank you.

Rebecca: Today our teas are…

John: Black raspberry green tea.

Rebecca: Kristina, what are you drinking?

Kristina: I’ve got my usual Diet Coke.

Rebecca: And I am drinking English Afternoon tea.

John: Could you tell us a little bit about this class of approximately 5000 students?

Kristina: Sure, we have two courses: we have Introduction to American government and then we have Introduction to Texas Government… both of which are required by our Higher Education Coordinating Board here in Texas. And it gives the students the opportunity to learn about our basic political system, and we throw in a little bit of political science theory, and it makes sure that our students leave their public university degree knowing something about how their government works and how they could participate in their government if they chose.

Rebecca: How is it 5,000 students large? [LAUGHTER]

Kristina: The State of Texas does require each of our students to take both of these before they can graduate with a public university degree, and with a large university like Texas Tech, we’re at about 35-36,000 students right now. What that means is that these massive freshman classes all need to get these two courses out of the way and it ends up being about 5,000 of our students every semester needing to take the two courses.

John: How do you manage a class so large… in terms of structure? What type of support do you have in terms of TA’s, co-instructors, or other assistants?

Kristina: We operate under what I call the “umbrella method.” So as an Economist (I’m a trained Economist), I definitely subscribe to David Ricardo’s idea about specializing and trading. So, rather than having each professor as an island where they’re handling every aspect of their 200 or 250 person course, instead we decided to specialize the roles that we needed, so that each person is handling one task for all of the students. So, I am at the little peak of the umbrella and I handle the course content. I make sure that we work with the publisher to get the students their materials and that it’s all delivered appropriately and I work with the various institutions on campus that need reporting data, assessment data, enrollment information. I have a co-instructor who handles the more day-to-day tasks of: students emailing… asking about course policies… asking for exceptions to course policies… questions about the content itself. He handles all of that for all the 5,000 students. We have two course assistants who just handle the mechanics of the course. So again, they get a lot of student emails as well. They deal with the settings in our learning management system… which we use Blackboard. So when a due date needs to be set or changed, they deal with that. And then we have TA’s, we supervise about 24 TA’s, each of them doing grading for the written work. It was really important for us that our students not only be doing multiple choice exams… we wanted to make sure that their they’re doing written work… because that’s, in my opinion, a better way to evaluate student learning. So each of the TA’s is grading one of the sections of the online course. So again, we’ve specialized out each task to make sure that one person isn’t required to do publisher and assessment and emails and content and grading for one section. It’s a lot more efficient, we think, to do it in a more specialized way.

John: Is it one large section or does it consist of multiple smaller sections?

Kristina: It’s multiple smaller sections. A lot of that is because we asked our students to do discussion questions with each other and it’s a little bit overwhelming to ask them to discuss with 2,500 other students. [Laughter] So, it ends up being usually 12 to 14 sections of each of the course. So 12 to 14 American Government, 12 to 14 Texas Government.

Rebecca: What’s the difference between how you teach your class and a MOOC?

Kristina: Yes. So, “MOOC” is definitely a dirty word these days. MOOCs really rose in popularity a few years ago. The idea was to create these just huge open online sections that would let anyone enroll and complete content as they pleased and either get credit or not, depending on how the course was set up. So we distinguish ourselves from a MOOC… first of all, because it’s not an open course. You have to be a student enrolled at the University to take this course, but also we don’t consider ourselves to be massive because we separate these courses into smaller sections, manageable chunks that our TA’s can grade. We also place a lot of value on the interactions that students have… so students interacting with each other (and often that’s done via discussion boards)…. students interacting with the content (and that’s done at their own pace asynchronously as they go through their course content)… and students interacting with the instructor… and that’s both to ask the instructor questions either on the course content or about the course mechanics… but also to provide feedback so that the instructor can take that information and then decide what to do with it. So, as we receive feedback, some of the feedback is, “your class is too hard” and we usually don’t really do much to address that… but if there are specific things: “the content is confusing, things are worded in different ways” then we can interact back with the content and the students to make sure that we are addressing these issues as they come along.

Rebecca: With such a complicated umbrella structure, how does the student know what person to communicate with?

Kristina: Well, sometimes they don’t, and we do have a really good system for navigating students to where they need to be… but we just try to include at the beginning of the semester both on their landing page (their home page when they enter in) and tell them, “Here’s the people that you can contact and here are the kinds of questions that they can help you with…” …and we also try to make sure to include a welcome video at the beginning that we ask students to watch… but give them an idea of how does this course work… who are you going to encounter… who you’re going to talk to… and what’s the most efficient way to get you through this course. I think a lot of times with these introductory mandatory courses, the students and the professor are at opposing goals. The student wants to get through this course as quickly as possible so they can check the box on their degree plan and move on. The professor wants the student to learn something about the discipline that they’ve devoted their lives to. So, I spent a lot of hours writing this content that matters to me a lot and and we tried to tailor the content to where we are. We’re in west Texas and when we talk about international trade, we talk about cotton because that’s what’s grown out here. So, I’m so passionate about the subject and if we aren’t aware that the student and the professor are at opposing goals, then it can lead to frustration for all of us. The students are frustrated because they think I’m asking too much and I’m frustrated because I don’t think they care enough.

So what we try to do is just make sure that we have a set of things that we want our students to accomplish, and some of those are content related: “Who’s your representative? Who are you going to contact if you have a problem?” …that’s something I want my students to know… how you go about registering to vote…. that’s something I want my students to know… political science concepts broadly about what influences judicial behavior… those are the things I want my students know. But I also value them learning things like meeting deadlines, and emailing professionally, and managing their own time, and that’s something that an online course is really uniquely situated to teach. So, we designed the course, knowing we want our students to learn some things. They may not want to engage with the content more than we require, so we give them a way to check the box… get it through their degree plan… while still making sure that they’re learning those concepts that are important to us.

John: What types of activities would students engage in each week in this course?

Kristina: It’s a very typical online course in the sense that the students are asked to do some readings and do some quizzes and write some short answer assignments. The one thing we’ve found to be most successful after doing this for 5 or 6 years… what we found to be most successful is chunking the content… and that’s a really popular phrase in online instructional design these days…. making the content into small manageable pieces. So I’m a millennial, I have to admit, and my attention span is about the attention span of a goldfish. So, I understand what it’s like to not want to watch a 25-minute video of someone lecturing to me. So, we really tried to take the concepts and distill them into manageable chunks. A 5-minute video talking about campaign financing rather than a 25-minute lecture… and at the end of the day, it facilitates that goal of getting the students to know what we need them to know without asking them to engage more than they’re willing to engage for a course that they just view as a checkbox.

Rebecca: I know that you wrote a paper on best practices for online courses. Can you summarize some of the key best practices that you’ve implemented in this class?

Kristina: Absolutely. The work that I’ve been doing on best practices… it really does stem from working with people who are trying to help us make our courses better. And I think a big problem in online education and instructional design is that it’s very new… and a lot of times when we think about what are the best practices, most of the evidence is just based on anecdote and experience. And so there’s something extremely useful about sitting down… I mean that’s what you’re doing with me right now… sitting down and listening to what I’ve done and what’s been successful for me…. and then, hopefully, listeners can take what they think will be helpful to them and apply it to their own experience. But I hesitate to say that just taking what has been a good experience for me, because it’s worked in my situation, could then be said to be a best practice for everyone else; that because our umbrella model is working really well for us, it is therefore the best practice. So what I’ve been doing with some co-authors is taking apart these ideas of best practices and empirically testing them to see whether they hold up to a quasi-experimental design.

The most recent work I have (that’s under review) looks at the organization of tools in a learning management system. So my co-author was teaching an online course and was told by his learning management system professionals that he wasn’t allowed to change the order of tools. So, the syllabus, the calendar, the grades– these sorts of things, he was supposed to leave them in a certain order because it was the best practice and he thought, “I don’t believe that… I don’t believe that that’s really a best practice…” So we tested it. We looked at when you manipulate the order, does it change the way students feel about their course? And does it change their performance? And we found it doesn’t and this is initial findings, of course, we do want to see these replicated before we were to say there is no best practice. But I think what most of my research is finding, when it comes to best practices in the order in which students experience content or the kinds of verbs we use when we describe what they’re going to do, it may not always be transferable across courses, across institutions so we need to be careful when we’re saying, “this is the best practice” as opposed to, “this is a practice that worked well for me and take what you will from that.”

John: Have you done any other research on best practices in terms of testing? With that large enrollment, you’ve got some nice possibilities of doing some randomized controlled experiments.

Kristina: Absolutely, and I think my IRB is getting tired of my requests to explore these differences in pedagogical practices. One paper that was recently accepted at the Journal of Political Science Education (and should be published this summer) looks at learning objectives. We’re often told as faculty members that we need to write learning objectives in a certain way. Bloom’s taxonomy, I’m sure you’ve heard of this, where we’re asked to use certain verbs to describe what we want our students to learn…. and my co-author, Whitney Manzo, who’s at Meredith College in Raleigh… we really wanted to dig into this. We argue that learning objectives are only useful to the extent that we all have a higher education community share an understanding of their purpose… of their definition… and to the extent that they help students learn better… learn more… perform better. And as we did interviews and surveys with students, faculty members, and assessment professionals, we found that there’s simply not a shared definition, and not a shared perception of why we have learning objectives…. and using learning objectives that are written and presented in a different way in a classroom didn’t seem to change the way the students perceive them or how they performed in the course. So, it’s not that my research is trying to say that, it doesn’t matter, it’s a free-for-all, you can do whatever you want. I think what my takeaway is… that we should be able to place a little bit more trust in our faculty members to know the nuances of their own classrooms… their own situations… their own institutions… and be able to listen to faculty members more in saying how they think something like Bloom’s taxonomy… or learning objectives.. or ordering of tools in an online course…. listening to faculty tell us what they think is the most useful in their situation.

Rebecca: In classes this large, cheating is likely to come up as a concern, I would imagine. A wide variety of web-based services have appeared to help facilitate academic dishonesty, including sites to facilitate plagiarism. What challenges have you had dealing with academic honesty and what tools have you implemented in your classes?

Kristina: Academic dishonesty is absolutely rampant and not only in an online course, I observe academic dishonesty in face-to-face courses as well. But sometimes, online courses just make it that much easier to get away with cheating. There are lots of tools that we’ve used, Turnitin.com and other plagiarism detection softwares. Sometimes I feel like your own eyes and experience as a faculty member are just as good, if not better, than these detection services because students have learned how to trick them. Students have learned that if you use a thesaurus and change the words, then the Turnitin won’t catch it.

John: And there’s even some websites that will do that automatically… where you can submit a paper and it will automatically change some of the words for you.

Kristina: Oh great… yeah, exactly. So it’s making it much easier to get away with cheating. Sometimes, if I just see a sentence that’s suspicious…with 5,000 students, I’ve seen the Wikipedia page on supply-side economics hundreds of time…. because now I’ve seen the words from it, either in those words or slightly altered in so many of my students writing. I think some level of academic dishonesty is inevitable whether we’re in a face-to-face course or not…. and in some ways, online courses make it easier for me to catch academic dishonesty. So in a written paper where a student hands me ten pages printed out from a printer, it’s a lot more effort for me to Google a sentence that looks suspicious than it would be if I just copied and pasted it out of the learning management system. So maybe it’s facilitated dishonesty, but it’s also made it easier for me to catch.

John: It’s a continuing arms race to some extent.

Kristina: [LAUGHTER] It is.

John: One thing I ran across a couple of years ago is that you can change individual letters, do a global search and replace with a different character set and that will defeat SafeAssign, Turnitin, and most of the other automatic detection services. But one of the clues there is that you end up with a plagiarism rating of zero percent, which is something you never see because of bibliography graphic references and similar things, it was interesting. I had one student do that in two different papers in two of my classes.

Kristina: Yes, the students are definitely ingenious in how they can come up with ways to cheat the system. Sometimes I think that if they would put as much work into their coursework as they did in trying to cheat, they would actually end up doing a lot better.

John: [LAUGHTER] Yes.

Rebecca: What steps have you taken to keep your graders and co-teachers and everybody in your big umbrella on the same page so that students have somewhat of a consistent experience?

Kristina: I think that this inter-rater reliability is always going to be a problem and it’s a problem no matter what. If we were to do this face to face and we had an instructor with a TA handling an individual section of 200 or 250 students and teaching it in a lecture hall, the content would be different… the expectations would be different… the tests would be different… the papers would be different… everything about the course would be different. So moving to this umbrella method has allowed us to ensure some consistency across sections. Now we still certainly allow faculty members who want to teach this course face-to-face to do so and it’s an academic freedom issue in that if they don’t want to use these materials, they certainly don’t have to. But it is nice for us to be able to generate some comparable assessment data that we can see are things changing over time and, if so, is that because the students are changing ?or is it because something about our course is changing? The ways that we try to ensure some consistency… what we can’t control… we do trainings with our graders… and we got this idea from the AP program where they essentially have retreats, where they sit around training these AP scorers on how to be consistent with these rubrics. So that’s one thing that we’ve done in trying to ensure that the graders are grading consistently. We also just monitor throughout. So, not only do I look at the general averages… are some graders scoring more or less strictly… but also spot-checking assignments and trying to do a systematic sample where we check every certain assignment to see if it’s consistent with what I would expect and what we train them to do at the beginning. And if we notice inconsistency it’s not punitive… we don’t threaten to fire TA’s who aren’t grading consistently… but it does give us an opportunity to say, “Hey, I think you’re grading these a little bit too harshly” or “a little bit too generously” or “I think you’re focusing on the wrong aspects of this assignment, you should be focusing on something different.”

Rebecca: One of the other things that you’ve presented on is online accessibility. We’re certainly working on that here. I’m working with faculty and other colleagues in other departments on some accessibility policies and things like that. How have you encouraged this to happen in your program and in your courses?

Kristina: It’s always difficult to tell faculty what they have to do. I don’t know if you’ve had much success going to a faculty member’s office and saying, “Guess what, you have to do this now” and them being like, “Great! I’m in, I want to do it.” I haven’t had a whole lot of success at that approach. Some of what I’ve been doing with my online course…. it’s kind of just accepting that this is how it is and this is what we have to do and so there’s no sense in trying to fight it. We’ve got to make our courses accessible to students with disabilities and there’s no reason to imagine that we wouldn’t want to do so. So we just make sure that all of our videos either have captions or transcripts. We make sure that all of our content that might not be easily accessible for a student with a disability to have an alternative method of accessing it if they need it. We try to avoid time limits on multiple choice questions because of students who might need extra time to complete their work. And so we just, in general, try to avoid the time limits altogether and make it equally accessible for all students, whether they have a disability or not. In terms of trying to encourage other faculty members in my department, who are either designing upper-division online courses or graduate-level online courses, making it less of a burden… providing resources and options for faculty… that’s been really successful. So if you just tell a faculty member you need to make your course accessible, that’s kind of an overwhelming request. There’s a lot to accessibility. So what we try to do is provide resources, ideas, support, ways to still do the same kind of content without running into accessibility problems. That’s been really successful… and taking just a more step-by-step approach. We know that the Americans with Disabilities Act requires everything to be compliant, but what we hope to always show is a good faith effort. So, whether we’ve achieved it perfectly every time or not, I guarantee if somebody combed through every course I’ve ever done, they’re gonna find something that’s not quite in compliance… but we’re making a good-faith effort and anytime a student brings to us an issue that they’re having, we work with the Student Disabilities Office to rectify it as quickly and as completely as possible.

John: With the umbrella framework for the course, it would seem that at least for these two courses, you have more control because you’re the one designing all the materials. So, you have at least some control over all the sections in terms of having the common materials compliant.

Kristina: Exactly, and it also helps that our Students with Disabilities Office, because of this umbrella model, knows exactly who they can call if there’s an issue that a student’s having. They know they can call me at any time, they know that I will always make a good-faith effort to keep things in compliance.

John: Do you teach any upper-level or graduate courses there?

Kristina: Yes I do, and others in our department also teach upper-division and graduate courses. What I envision when designing these courses is a political scientists favorite thing, which is a two-by-two matrix.

[LAUGHTER]

We love our two-by-two matrices and I’m happy to draw out this two-by-two matrix so that you guys can have it in your supplementary materials. But when I think about the purpose of the course and the customization of the course… so we can have a course that’s intended to be very in-depth and a deeper understanding and engagement with content (which we would want in a graduate-level course or upper division) versus something that, as I mentioned with our lower division courses., we’re seeking some basic understanding and some basic behaviors to help students learn what we want them to know, while they’re able to still satisfy those requirements. And so that’s one dimension. We can also think about the dimension of: “How customized do we want our content to be. So do we want to use something that’s sort of off-the-shelf or canned?” Or do we want to use something that we’ve written every word… we’ve written all of the quiz questions… all of the readings. And so I think every online class can kind of be placed somewhere in this 2×2 matrix. When we’re doing our introductory courses, we’re looking at maybe a lower level of student engagement but we still have a really high level of customization. So, as I mentioned, we’re in West Texas, I make sure we talk about cotton disputes when we talk about international agreements and international negotiations. In our graduate level courses, we move over to the to the high level of engagement, to the in-depth understanding… and then depending on what the faculty member wants, we can either do a fully customized version of a course where we write most or all of the content. Or we can use some existing resources… and there are publishing companies out there that have a lot of content that’s really good and that’s really ready to be used and it’s really highly interactive and engaging. So, we try to establish what’s the purpose of our course and what is our content that we want to create versus we want to use existing content… and then where does this course fit in. And after we’ve placed it in that matrix, then we can decide how to move forward in designing the course.

Rebecca: Do you work with instructional designers as you’re designing these courses or is that the function that you provide?

Kristina: It’s somewhere in the middle. So I’ve worked with our instructional designers here at Texas Tech and they are very supportive. They have a great way to make sure that they’re providing the level of help that you want and need. There are plenty of faculty members (and I’ve worked with them) who want to assign some readings and then have a final exam and call it an online course. And our instructional designers exist because we all know that that’s not going to work. SACSCOC is going to shut us down if that’s what our online courses look like. And so when I worked with instructional designers, usually once they see where we are in our course development… the fact that we’ve developed a lot of courses before… they provide us a high level overview… they give us some suggestions… compliance issues… and they let us go on our way. But when we have faculty members that have less experience, they are a lot more hands-on. Now I’m not sure they really liked all my learning objectives research… I don’t think they liked that research very much… but they’ve definitely been supportive and interested in hearing what it is that we’re doing here in Political Science.

John: Well they may not like it, but it could become part of their future dissemination that if you find significant results, it can help them improve all the courses there and more broadly.

Kristina: Absolutely.

John: Now you’ve received, I think, an internal grant for “engaging students in global governance and communication, hosting a lecture series and sponsoring in-depth, archival, and undergraduate research as a part of the university’s quality enhancement plan.” Could you tell us a little bit about that?

Kristina: Sure, so our quality enhancement plan, that’s QEP, it’s a part of SACSCOC program. The goal is to identify a way to enhance student experience and then dig in and make the student experience at our university better. So our QEP plan is about communicating in a global society and our Center for Global Communication offered a grant to programs that were willing to engage in something that would touch a lot of students and would encourage engagement with this global communication. So we have several levels of engagement that our students can participate in. In our introductory course, the students are asked to watch a lecture about communicating in a global society, about having relationships with those who are different than you — from a different country or background. And all of the students who take these introductory courses are exposed to that content, so that’s a great way that… even though maybe it’s in that lower level of engagement in the 2×2 matrix, it’s reaching a lot of students. But we also sponsor a lecture series and this is where we’ve brought in, typically political scientists, but generally social scientists have all been considered to speak as part of our lecture series. And so we’ve had people talk about terrorism and how social media can facilitate terrorist recruitment. We’ve had people talk about presidential travel as a form of global communication. So, when President Trump goes to Saudi Arabia first, as his first international visit, what kind of communication does that send to the world? This lecture series invites our students to come in and get a little bit more in-depth experience with global communication and that’s the way our online students can feel like they’re not just isolated at home… that they’re not participating in a university experience. We invite our online students and we usually get two to four hundred students at each of these events… so they’re wildly successful. In addition, after the lecture series, we’ve offered students an opportunity to participate in undergraduate research and we’re even able to sponsor two of our students to attend a national social science conference under the supervision of a faculty member to present their own research or at least be exposed to other research, related to global communication. As political scientists, we’re very well situated to expose students to the idea of global communication and as a large online program that can reach a lot of students, it also helps us to get the message out about the fact that this is an important part of their education.

Rebecca: Sounds great! It’s a really unique case study.

John: It seems like you’re reaching quite a few students who might not be reached by traditional educational programs.

Kristina: Yeah, I think that this kind of program might be new and different right now, but this is where education is going to be going, as we have the need to educate more and more students, college isn’t something that’s only for wealthy upper-class men and and women. It’s for everyone now… and we’re going to try to meet students where they are. Online education is where the future is and when we see students who are non-traditional trying to come back and get degrees… they have full-time jobs… they have families… they’re not able to go to class like a traditional 18- or 19-year old student is going to be able to attend classes during the day. I really think that this could be a potential equalizer for students. Not only in accessing content and getting degrees, but in learning some of these really valuable skills in how to interact in an increasingly online world.

John: And the rate of return to a college degree is the highest we’ve ever observed. We’re seeing not a lot of jobs out there and not a lot of job growth for people with high school degrees and high school dropouts. We need to do more to get more people to college and certainly the approach you’re taking there is a very efficient way of bringing education to a large number of people.

Rebecca: Well thanks so much for joining us Kristina, it was nice to have you back and it’s always nice to hear what you’re working on.

John: If you’ve enjoyed this podcast, please subscribe and leave a review on iTunes or your favorite podcast service. To continue the conversation, join us on our Tea for Teaching Facebook page.

Rebecca: You can find show notes, transcripts, and other materials on teaforteaching.com. Music by Michael Gary Brewer.