The time between semesters is a good time to engage in reflective practice. In this episode, we take a look back at our teaching practices and student learning during the Fall 2022 semester as we prepare for the spring 2023 semester.

Show Notes

- Donna the Buffalo

- Student Podcasts – Tea for Teaching podcast. Episode 242. June 1, 2022

- PlayPosit

- iClicker Cloud

- Research on hybrid teaching effectiveness

- Joosten, T., Harness, L., Poulin, R., Davis, V., & Baker, M. (2021). Research Review: Educational Technologies and Their Impact on Student Success for Racial and Ethnic Groups of Interest. WICHE Cooperative for Educational Technologies (WCET).

- Means, B., Toyama, Y., Murphy, R., Bakia, M., & Jones, K. (2009). Evaluation of evidence-based practices in online learning: A meta-analysis and review of online learning studies.

Transcript

Rebecca: The time between semesters is a good time to engage in reflective practice. In this episode, we take a look back at our teaching practices and student learning during the Fall 2022 semester as we prepare for the spring 2023 semester.

[MUSIC]

John: Thanks for joining us for Tea for Teaching, an informal discussion of innovative and effective practices in teaching and learning.

Rebecca: This podcast series is hosted by John Kane, an economist…

John: …and Rebecca Mushtare, a graphic designer…

Rebecca: …and features guests doing important research and advocacy work to make higher education more inclusive and supportive of all learners.

[MUSIC]

John: We’re recording this at the end of 2022. We thought we’d reflect back on our experiences during the fall 2022 semester. Our teas today are:

Rebecca: I have blue sapphire tea once again, because it’s my new favorite. And I have discovered that the blue part are blue cornflowers. That’s what’s in it. So it’s black tea with blue cornflowers.

John: And I have a spring cherry green tea, which is a particularly nice thing to be having on this very cold wintry day in late December, in a blue Donna the Buffalo mug, which is one of my favorite bands.

Rebecca: We had a few things that John and I talked about ahead of time that we thought would be helpful to reflect on and one of them is our campus, like many SUNYs, is in the process of transitioning their learning management systems. And we did move to Brightspace for the fall semester. So how’d it go for you, John?

John: For the most part, it went really well. Returning students were really confused for about a week as they learned how to navigate it. But overall, it went really smoothly, it helped, I think, that I had taught a class last summer in Brightspace, so I was already pretty comfortable with it. But, in general, it had a really nice clean look and feel, it brings in intelligent agents where we can send reminders to students of work that’s coming up that’s due, reminding them of work that they’ve missed that they can still do, and just in general, automating a lot of tasks so that it seemed a bit more personalized for students. And that was particularly helpful in a class with 360 students. And also, it has some nice features for personalization, where you can have replacement strings, so you can have announcements that will put their name right up at the top or embedded in the announcement. And that seemed to be really helpful. One other feature in it is it has a checklist feature, which my students, periodically throughout the term and at the end of the term, said they really found helpful because it helped them keep track of what work they had to do each week.

Rebecca: Yeah, I used the checklist feature quite a bit, because I have pretty long term projects that are scaffolded and have a number of parts. And so I was using the checklists to help students track where they were in a project and make sure they were documenting all of the parts that needed to be documented along the way. I think generally students liked the look and feel of this learning management system better. But I also found that I was using some of the more advanced features and a lot of their other faculty were not. And so that difference in skill level of faculty using the interface, I think, impacted how students were experiencing it. And that if their experience was varied, they struggled a bit more, because it was just different from class to class. So I know that students struggled a bit with that. But it was also my first time teaching in that particular platform. From a teaching perspective, I think it went well. I found it, for the most part, easy to use and I like the way it looked. But students and I definitely went back and forth a few times about where to put some things or how it could be more useful to them. And we just negotiated that throughout the semester to improve their experience. So I think that was really helpful.

John: You mentioned some of the more advanced features, what were some of the advanced features that you used?

Rebecca: Yeah, I mean, I used the checklist, which not a lot of students had in some of their other classes. I know you used it, but I don’t think a lot of faculty were using those. I had released content, just I know you also use some of these things, too, but a lot of other faculty were just like, “Here’s the content. Here’s your quiz.” …and kind of kept it pretty simple. But I teach a stacked class, so I had some things that were visible to some students and not to other students. Occasionally I’d make a mistake there, so that caused confusion.

John: And by a stacked class, you meant there’s some undergraduates and some graduate students taking the same course but having different requirements?

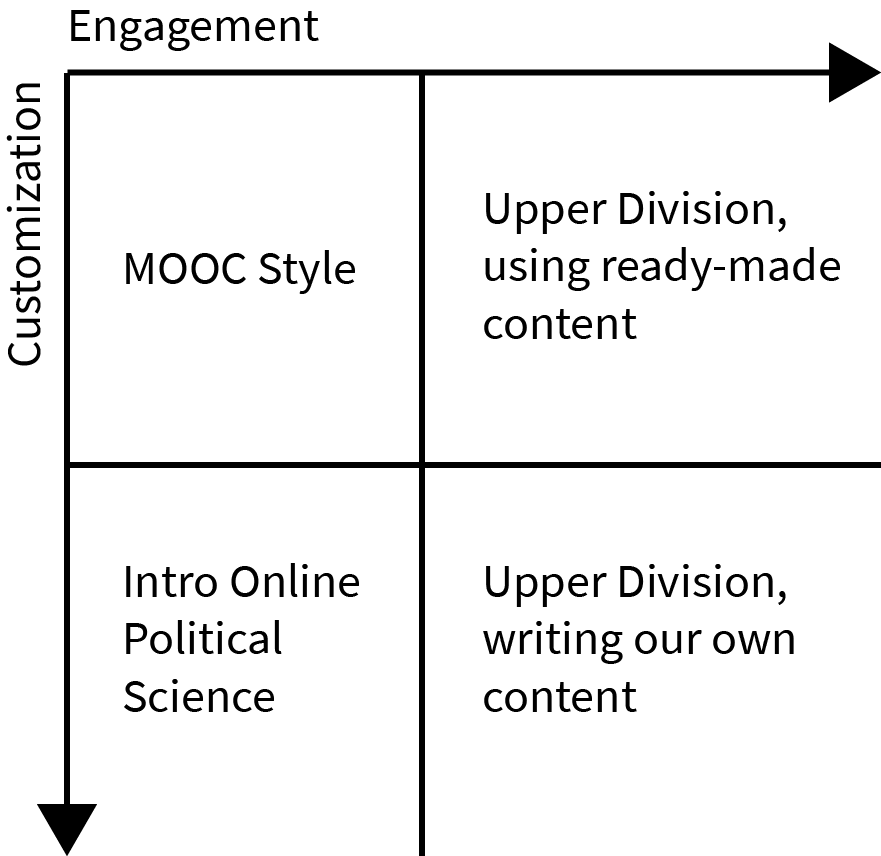

Rebecca: Yeah, and also different levels. So within both the undergraduate and graduate students, I’ve beginning students and advanced students. So there’s really kind of four levels of students in the same class.

John: It does sound a bit challenging…

Rebecca: Yeah.

John: …especially on your side.

Rebecca: Yeah. So it’s easy to sometimes make mistakes, which can certainly result in confusion. I think students were also just trying to figure out the best way to find stuff like whether or not to look at it from a calendar point of view, or from a module point of view. They were just trying to negotiate what worked best for them. And there were some syncing issues between the app and what they were doing with checklists in particular. So it caused a lot of confusion at the beginning, but we figured out what it was and that helped. So new things, new technical challenges result in some learning curves. But I think, throughout this semester, we worked through those things and students were much more comfortable by the end of the semester.

John: And by next semester it should be quite comfortable for pretty much all students.

Rebecca: Yeah.

John: So what went well for you, in this past semester?

Rebecca: I had a couple of really good assignments. Some of them were experimental. [LAUGHTER] I wasn’t really sure how they were gonna go and I was pleasantly surprised. One practice I continued, that continues to go well, is using warm ups at the beginning of my class for design and creativity. And that seems to continue to be very helpful for students. I teach longer class periods than a typical class because it’s a studio. And so transitioning into that space was helpful for students, and also starting to teach them ways to foster creativity when they feel very stressed or have a lot of other things tugging on their minds they also reported was very useful to just learn some strategies. We did things about prioritization, creativity, planning, related to the projects that we were doing. So that continued to be really useful. And then I did a brand new project that I’ve never done before. And the work was fantastic for the most part. I collaborated with our campus Special Collections and Archives. And we made a couple sets of archives available to students that were digitized. And then my students created online exhibitions and focused on that experience, so that it’s not just “Here is five things,” [LAUGHTER] but rather like it’s a curated experience that had kind of exploratory pieces of it. And that went really well, students got really curious about the materials in the archives. These are students who maybe have never really took advantage of these kinds of library resources before and started to learn how to dig into understanding these primary sources better as well. So that was really exciting.

John: What topics were the archives related to?

Rebecca: There were two collections. One of them was a scrapbook from the early 1900s that had a lot of example trade cards, or industry cards, and advertisements. And so in a design class that became interesting materials to look at. And then another collection was digital postcards from the area. So they were looking at the city of Oswego and the campus at different time periods. And they found that to be kind of interesting. And there’s others that we’d like, but we went with ones that were [LAUGHTER] primarily digitized already, to make it a little easier.

John: And what did they do with those?

Rebecca: They had to pick a collection they wanted to use. And then they had to select at least 10 pieces from that collection, come up with a theme or some sort of storyline that they wanted to tell about those objects, and then they had to create this online experience. So they created websites, essentially, that had interactive components. And there were a wide range of topics. One student did something on women’s roles in the early 1900s through media. Another student focused on like then and now. So they took the postcards and then they went and took their own photos of those same places and did some comparisons with some maps and things. Some that were telling the history of the institution, which was kind of interesting. The history of boating in the area. So people picked things that were of interest. Snow was a big topic [LAUGHTER] … there’s a couple students that did things about snow and documentation of snow over time. But they were good, they were really interesting works. And we’re looking to get those up in a shared OER format. We’re getting close on being able to get that and share that out, but we’re hoping to deposit a copy of the projects as a unified whole back to the archives and then have them live online as well.

John: Very nice.

Rebecca: How about you, John? I know you were continuing your podcast project.

John: In my online class, which is smaller, it’s limited to 40 students, it worked really well this time. One thing that was different is that nearly all of my online students were genuinely non-traditional students. They were mostly older, by older I mean in their late 20s, early 30s. And they were just very well motivated and hardworking, and the class in general performed extremely well. They got all their work done on time, they were actively engaged in the discussions, and they really enjoyed creating the podcast in ways that I hadn’t seen as universally in past classes. Several of them mentioned that they were really apprehensive about it at first, but it turned out to be a really fun project. Because it’s an online class, they didn’t generally get to talk to other students, but they worked asynchronously in small groups, typically groups of two or three, on these podcasts and it gave them a chance to connect and talk to other students that they wouldn’t normally have outside of discussion boards in an online class. And they really appreciated that. And they really appreciated hearing the voices of the other students in the class. So that worked especially well.

Rebecca: I know you’ve also had, in some of your classes in the past few years, when there’s more online learning happening that maybe wouldn’t typically be a “distant learner” or someone who would choose to be online. And so this semester, you’re saying that the students who were in this class were actively choosing to be in an online class and that maybe made a difference.

John: They were students who generally were working full time and often, under really challenging circumstances were engaged in childcare, working full time, and taking three or four or five classes, sometimes working a couple of jobs. And yes, in the past, a large proportion of the students in online classes were, even before the pandemic, dorm students who weren’t always as well motivated as the students who were coming back to get a degree at a later stage of their life, who had a career and perhaps wanted to progress in that career. And during the pandemic, so many students were in online classes who really didn’t want to be there, it was a very different experience. So we moved past that now, or at least in my limited experience with a very small sample last semester, the students who were online were students who benefited greatly from being online and actively chose to be online. It’s a much better environment when students are able to take the modality that they most prefer to work in, for both them and for the instructor.

Rebecca: Yeah, then you’re not pulling people along who haven’t had that experience of taking an online class before, as well as trying to get them to do the work. Were there other practices or activities or other things that you employed in your class that worked particularly well this semester?

John: in general, I didn’t make too many major changes in the class because the transition to Brightspace alone was a bit of a challenge on my part, because it did require redoing pretty much all the materials in the class. But on both my large face-to-face class and my online class, I use PlayPosit videos to provide some basic instruction in the online class and to help facilitate a flipped class in my face-to-face class, where I have a series of typically two to five short videos each week in each course module with embedded questions. And students generally appreciated having those because they could go back and review them, they could go back and if they didn’t do too well on the embedded questions, they could go back and listen again or look at other materials, and then try it again. And basically, they had unlimited attempts at those and they appreciated that ability. Those were the things I think that probably went best. It was overall a challenging semester.

Rebecca: What was one of the biggest challenges you think you faced this semester as an instructor, John?

John: The two biggest challenges that I think are very closely related is… the class I was teaching both online and face to face is primarily a freshman level class, an introductory class… the variance in student backgrounds, particularly in math and the use of graphs is higher than I’ve ever seen it before. Some students came in with a very strong background, and some students came in with very limited ability and a great deal of fear about having to do anything involving even very basic algebra or arithmetic even. And it made it much more challenging than in previous semesters. And I think part of the issue is that we’ve seen some fairly dramatic differences in how school districts handled the pandemic. The learning losses were much smaller in well-resourced school districts, then in others that were more poorly resourced school districts in lower income communities. When schools had fewer resources and when the students in the schools had limited access to technology, and so forth, the shift to remote instruction had a much greater impact on those students. And that’s starting to show up at a level that I hadn’t seen in the first year and a half or so of the pandemic; it hit really hard this fall. And the other thing is that a lot of the work that was assigned outside of class simply wasn’t being done. I’ve never seen such high rates of non-completion of even very simple assignments, where students would have five or six multiple choice questions they had to answer after they completed a reading. And between a third and a half of the class just chose not to do it. It was very low stakes, they had unlimited attempts to do these things, but many of them just simply chose not to. And I ended up with many more students withdrawing from the class than I’ve ever seen before.

Rebecca: So I think there’s a couple interesting things maybe to dig into a little bit more. We’ve certainly seen students prior to the pandemic have a fixed mindset about math skills, for example. But when we have a deep fear of things, it’s really hard to learn. How have you helped students work through the fear? And is the fear rooted in just not coming prepared? Or is it a fear of trying something new?

John: It’s a bit of both. Because they already come in with a lot of anxiety, it makes it more challenging for them to try the work outside of class. And that’s part of the reason for the use of a flipped classroom setting in my large face-to-face class, because we go through problems in class. We’ve talked about this before, but much of my class time is spent giving students problems that they work on, first individually, and then they respond using the polling software that we use (iClicker cloud) and then they get a chance to try it again after talking to the people around them. So it’s sort of like a think-pair-share type arrangement where, if they don’t understand something, they get a chance to talk to other people who often will understand it a bit better. And in the second stage of that process, the results are always significantly higher after students have had a chance to talk about it, to work through their problems, and so on. So having that peer support is one of the main ways that I try to use to help students overcome the fear when they see that other students can do this and they can talk to other students who can explain it at a level appropriate for their level of understanding, that can work really well. And then we go through it as a whole class where I’ll call on students asking them to explain their solutions, or I’ll explain part of it if students are stuck on something, and doing some just-in-time teaching. And normally, what that does is it resolves a lot of that anxiety, and it helps people move forward. But that just wasn’t working quite as well this time. And I’m not quite sure why.

Rebecca: I think although I’m not using the same kind of format in my classes, a design studio really does rely a lot on collaborative feedback and [LAUGHTER] interacting with other students and coming to class prepared having done something outside of class, and then we have something to give feedback on and continue moving forward and troubleshoot and things together in class. So we’re using class time also to work through the hard stuff rather than outside of class. So the interesting thing about doing that in class, and really a lot of active learning techniques in class, is that it does depend on students coming prepared and having done something ahead of time. And if they’re not doing that ahead of time, it really changes what can or cannot be done in class. And the other thing that I experienced related to that is, some students just reported a deep fear in sharing things with other students that I’d really not experienced before. In the past, that’s always been a really positive experience. And those who get fully engaged in that continue to say it was a positive experience, but there were some who would actively avoid any of those opportunities to share their work. I don’t know why. I think there’s two things, there are some students that just were not doing things outside of class. So they were embarrassed or didn’t want to have their peers think that they didn’t know what was going on, or they didn’t want to reveal that they were behind. And then there’s another group of students who actually were overly prepared and did all the things, but they have a deep fear of being wrong or not being perfect. And there’s a lot of anxiety around that. And so working through that was a real challenge for some of the students this semester as well. And I’ve always had a few students, they tend to be what you would think of as high-achieving students who sit in this category. But it seems like it’s actually a bigger number of students or like stress and anxiety around this perfectionism seems to be elevated, causing students to become paralyzed, or the inability to move forward.

John: And I would think that the stacked nature of your class would make that a bit more of an issue in terms of the variance between people who have more background in the discipline and those who have less,

Rebecca: Yeah, I have my class structured so that students are doing things in groups with students that are at a similar level in experience. So yeah, I experienced that in the classroom as a whole, but within their smaller groups, not as much.

John: I think one of the issues that may have affected my class is at the start of the class, I was in the early stages of recovery from a broken leg. So I was kind of just leaning against a podium or sitting on a chair near their podium for the first couple of weeks. But one of the things that was different for me this semester is normally when students are working on problems, I’m wandering all through the classroom, and I kept hoping to be able to do that. But it wasn’t really until the end of the semester that I could even stand and move around a little bit through the whole class. But I did miss the ability to interact with students and help them work through their problems in small groups as I wandered through the classroom. I was very lucky to have a teaching assistant who was able to move around, but it would have been better if we both had that mobility. And I’m looking forward to being able to wander through my classes this spring.

Rebecca: It’s interesting that you say that, John, because this was the first semester I was back in person. The last two years, I’ve taught fully online, synchronously but online, and one of the things I missed about the kinds of classes I teach is that during class, we are often working on projects, and I in person can easily wander around and see where students are at and bring students together and do impromptu critiques or technical things a little more easily than I was experiencing online because, although they may be working, I couldn’t see, kind of casually just walking by, I couldn’t intervene when students weren’t where they needed to be, or were struggling and just didn’t want to ask for help, because I didn’t know, because they didn’t tell me. But when it’s in person and I’m wandering the room, I can make those observations and do those interventions. I did notice that in my walking around and doing interventions this year is a bit different than it had been prior to the pandemic in that some students would actively avoid me if I was coming near them… It was like, “Oh, no, I have to go the bathroom” or they would just disappear. And I would miss them in a class period because they were gone when I was heading their way. And those were students who were struggling and struggled throughout the semester. So it was students that didn’t want to admit that they needed help or didn’t want people around them to know they needed help. And what’s interesting, related to that, is that during synchronous online learning, I could help people one on one without other students knowing, because I could easily pull them into a separate breakout room and we could privately talk in a way that, in a studio environment, is not as possible. So it’s an interesting dynamic, finding my way again, because the things that used to work don’t quite work the way they used to, as you were also describing, and then other practices I got very used to in a different platform also just aren’t available in a face-to-face format. So I’m interested to see how I might be able to balance these things, because I’m teaching more of a hybrid format in the spring, and I might be able to get a little bit of the best of both worlds. I’m not sure.

John: Well, there is some research that suggests that a hybrid teaching format works better than either face to face or fully asynchronous. So it’ll be interesting to hear how that goes.

Rebecca: Yeah.

John: I used to learn a lot about what students were struggling with just by overhearing their conversations as I walked along or by interacting with students directly. And I did miss that this semester and I’m looking forward to never ever having to deal with that again in the future.

Rebecca: Yeah, that was one of the things that I found most joy in being back in the physical classroom was just being able to wander around and greet students and have more low-key interactions with them, which also helps I think, with helping students move along and move through struggles.

John: One of the things you mentioned was the anxiety of students. And I know in my classes, students have become much more comfortable revealing mental health challenges. I’m not sure how much of it is that students are more comfortable revealing mental health challenges, or they are just experiencing many more mental health challenges than before. It’s good to know the challenges our students are facing. But when you hear dozens and dozens of such stories in a class, it can be a bit of a challenge in dealing with those.

Rebecca: Yeah, I found that I had a number of students who disclosed physical and mental health challenges they were facing this semester. And that did help me understand significant absences by those same individuals. And it also explained a lot of the struggle that they were experiencing in the coursework. Unfortunately, when students have so many things tugging at them, it’s really hard for them to focus on studies or to even prioritize that… they may need to prioritize some other things. And the student work or the students’ success in that population of students wasn’t as strong as some of the other students who were able to be present all the time and could do the outside work or were doing the outside work. I don’t know if it was “can” or “wanted to…” [LAUGHTER] …how that outside of class work was getting done. But those who are staying on top of the coursework as it was designed were more successful than students who had a lot of things that were causing them to be absent or to miss work.

John: And I know in our previous conversations, we’ve both mentioned that we’ve made more referrals to our mental health support staff on campus than we’ve ever had before. And it’s really good that we do have those services. Those services, I think, were a bit overwhelmed this semester and from what I’m hearing that’s happening pretty much everywhere. It’s often a struggle thinking about these issues. I know many times I’ve been awake late at night thinking about some of the challenges that my students are facing,

Rebecca: Students disclose things to us and then you do think about them, because we care about them as humans. Most of them are really nice humans. Some of them aren’t doing the coursework, but that doesn’t stop them from being nice humans that you care about. And it does take mental energy away when we’re thinking about these students and thinking about ways that we might be able to support them. And sometimes the ways to support them is completely outside of the scope of our jobs as instructors. And that’s disheartening sometimes, because there’s not an easy way for us to help other than a referral and you can see them struggling in class and you know why they’re struggling. But there’s not a lot of intervention, from a teaching standpoint, that can really happen sometimes with some of those students. And that’s just emotionally draining. Do you find that to, John? …that’s you’re thinking about them, but then you don’t really have a good solution for helping them often, academically anyway?

John: It’s a bit of a struggle, because you want students to be successful and you know, they’ve got some really serious challenges. One way of addressing this is to provide all students with the opportunity for more flexibility. And I know most of us have been doing this quite a bit during a pandemic. But one of the concerns that I’ve been having is that the additional flexibility often results in more delays in completing basic work that’s required to be successful later in the course, and the students who are struggling the most often are the students who put off doing the work to learn the basics that are needed to be successful. And I think that’s one of the reasons why I saw so many students withdrawing from the class this semester, much larger than I’ve ever seen it.

Rebecca: This is also, though, the first semester of a different policy related to withdrawals on our campus. And so some of that might be that students didn’t need to provide documentation to withdraw, like they would typically during the last few weeks of the semester. They were able to continue to withdraw until the very last day of class.

John: I’m sure that’s part of it, because many of the students who did withdraw had stopped working in the first week of the semester. And despite numerous reminders, both personal reminders and automated reminders using some of the tools built into our learning management system, they just were not responding. So I think some of them had made the decision fairly early to withdraw from the class.

Rebecca: Flexibility is an interesting thing to be thinking about. And I think both of us have advocated for levels of flexibility throughout the pandemic ,and prior to that as well. I don’t really have an extra penalty for students who miss class, their penalty is that they miss class and now it’s a struggle to keep up. And that often is the case. I provide flexibility in the kinds of assignments or what they might do for an assignment, some flexibility in deadlines, but the reality is, a lot of our classes are fairly scaffolded. And so if they don’t get the kind of beginning things, they’re not able to achieve the higher-level thinking or skills that we’re hoping that they can achieve by the end of the semester, because they haven’t completed those often skills-based tasks to help them practice things that they would need to perform higher-level activities.

John: I do have regular deadlines for some material in class. But what I do is I allow them multiple attempts at any graded activities where only the highest grade is kept. So they can try something, make mistakes and try it again, and, in many cases, do that repeatedly until they master the material. But there are some deadlines there along the way where they have to complete it. Because if they don’t, they won’t stand a chance of being able to move to the next stage of the course. To address issues where students do have problems that really prevent them from doing that, I end up dropping at least one grade in each of the grade categories. So that way, if students do face some challenges that prevent them from timely completing work by those deadlines, it won’t affect their grades. But I still encourage them to complete those assignments even if they’re not going to get a grade on it because they need to do that to be successful.

Rebecca: Yeah, deadlines can be really helpful for students who have trouble prioritizing or figuring out when to do things on their own. So deadlines are actually really important. Our scaffolding as instructors can be really important for students that need and want structure. And most students benefit from having structure in place and deadlines are part of that structure to help people move forward. But there can be flexibility within that. But if we provide too much flexibility, it becomes a challenge not only for students in terms of being able to level up in whatever they’re studying, but also in terms of faculty and workload and having to switch gears in terms of what you’re evaluating or giving feedback on. If we have to keep task switching, it’s a lot more straining than focusing on one set of assignments at a time.

John: One assignment where I did provide lots of flexibility was the podcast assignment, where I let students submit revisions at any time on that or submit late work because there were some challenges in finding times, and so forth. And I had a lot of work come in a month or more after it was originally due. And it did result in a lot of time spent during the final exam week and during the grading period after that, where I was spending a lot of time grading work that would have been nice to receive by the deadline, say 2, 3, 4 or 5 weeks earlier. But it did provide them with the flexibility that was needed, given the nature of the assignment, and one where they didn’t lose something in terms of their progress in the course, by submitting it late.

Rebecca: Yeah, projects are one of those things that I always encourage some continuous improvement on because often they’re so close. And if you just give them a little extra nudge or a little extra time, they can complete something at a higher level, especially when it’s something like a podcast or like my exhibit assignment that has a very public nature to it. We want students to feel like they’ve achieved something that they’re willing to share. And sometimes that means giving them a little extra time so that they can polish it. So it feels like it’s something that they can share and be really proud of. I guess that’s another argument for time and flexibility around non-disposable assignments. Right?

John: One of the other bright spots of the last several months was a return to more in-person conferences, where we got to see people that we haven’t connected with in person other than on Zoom or other tools for the last few years. And while we’ve attended many conferences over Zoom, one of the main benefits of in-person conferences are those little side conversations right after a session ends, or when you get to talk to the presenter after their session, or those conversations in the hallway over coffee. And it was really nice to return to those again, because that’s where a lot of the value of these conferences come from.

Rebecca: Yeah, it’s interesting how much maybe I started longing for some of that again. I was finally starting to experience that on campus, again, as more people have been more physically present on campus, which has been nice. Those casual conversations often lead to interesting projects together or new ideas or initiatives, they improve my teaching, and they just improve relationships over time. And I think I was feeling a pretty strong loss around that. And it was nice to have that reinvigorated.

John: And it was especially nice to be at these conferences where there are a lot of other people who are really concerned about teaching and learning. And it helps rebuild that community that changed its nature during the pandemic, when people were very actively connecting but it was over social media, back when we had Twitter [LAUGHTER] as a functioning social network platform, and through online interactions, but it’s nice to have those in person connections again.

Rebecca: Yeah, I definitely agree. I had started to feel, not totally burnt out, but I was headed in that direction and reconnecting with people in person has gotten me excited about possibilities in higher education again. I lost interest. I wasn’t even following news for a bit. I had really pulled back a little bit because I just felt overwhelmed by everything around me and it was hard to stay on top of what was happening. And I think some of these in-person conferences reconnected me to some of what was going on and some of the people who are doing that work. But it definitely got me re-interested in a way that I was just starting to become a little uninterested.

John: It’s a reinvigorating experience.

Rebecca: So should we wrap up, John, by thinking about what’s next?

John: Yes, what’s next for you, Rebecca?

Rebecca: [LAUGHTER] Nice toss there, John. [LAUGHTER] Next semester is likely to look different for me. I’m only teaching one class in the spring as I focus some more attention to some interesting initiatives in Grad Studies on our campus. And that one class is going to be hybrid and relatively small. So it’s a really different kind of teaching experience than I’ve had before. So I’m looking forward to that new adventure, or both of those new adventures. How about you, John?

John: I’m teaching the same classes I’ve been teaching for several years, but I’m looking forward to them, it’s going to be nice to work with upper-level students again. My spring classes are primarily juniors and seniors, mostly seniors. And it’s a nice time to reconnect with those students that I had often last seen in class when they were freshmen. And it’s really rewarding to see the growth that students have achieved during their time on campus, and to see the increase in their maturity and their confidence. And I’m very much looking forward to whatever project they’re going to be doing in the capstone course. Because for the last four years, they’ve done book projects, I’m not sure what we’re going to be doing. And I enjoy that uncertainty at this stage, which I have to say the first time I did, it was a little bit more stressful. But now it’s something I look forward to, letting them choose what they want them to have as a main focus of their course. So I don’t know exactly what’s next, but I’m looking forward to it.

Rebecca: That’s wonderful. I’m thinking that my spring classes are all advanced students, which doesn’t typically happen, and so I’m really looking forward to the opportunity of taking a break from a stacked class and actually just teaching a smaller group of advanced students and allowing them to take me on an adventure, which I know it will be. And I look forward to more of that mentor kind of role in that course.

John: And I’m looking forward to more episodes of the podcast. We continue to have some really good guests coming up and these discussions are something I always look forward to.

Rebecca: And definitely something that has kept both of us, I think, afloat during this pretty challenging time over the last few years.

John: Definitely.

[MUSIC]

John: If you’ve enjoyed this podcast, please subscribe and leave a review on iTunes or your favorite podcast service. To continue the conversation, join us on our Tea for Teaching Facebook page.

Rebecca: You can find show notes, transcripts and other materials on teaforteaching.com. Music by Michael Gary Brewer.

[MUSIC]