As faculty, we engage with education technology as it relates to our classes but rarely consider the larger EdTech ecosystem. Dr. Rolin Moe, the director of Academic Innovation and an Assistant Professor at Seattle Pacific University, joins us to discuss the politics, economics, and culture of EdTech.

Show Notes

- Veletsianos, G., & Moe, R. (2017). The rise of educational technology as a sociocultural and ideological phenomenon. Educause Review.

- Pappano, L. (2012). The Year of the MOOC. The New York Times, 2(12), 2012.

- David Brooks, “The Campus Tsunami,” New York Times, May 3, 2012. (Source of the John L. Hennessey “tsunami” statement)

- Duke University Talent Identification Program

- Boyer, E. L. (1990). Scholarship reconsidered: Priorities of the professoriate. Princeton University Press, 3175 Princeton Pike, Lawrenceville, NJ 08648

- Phillips, Matt and Karl Russell (2018). “The Next Financial Calamity is Here: Here’s What to Watch.” The New York Times. September 12.

- Personalized Learning and Adaptive Teaching Opportunities (PLATO) Program

- Sasha Barab – Quest Atlantis

- Oregon Trail – Wikipedia page on the MECC Corporation and the Oregon Trail game

- Vygotsky, L. (1987). Zone of proximal development. Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes, 5291, 157.

- Moe, Rolin (2017). “All I know is What’s on the Internet.” Real Life. January 17.

- WordPress

- Lynda.com

- Skunk Bear – NPR

Transcript

John: As faculty, we engage with education technology as it relates to our classes, but rarely consider the larger EdTech ecosystem. In this episode we examine the politics, economics and culture of EdTech.

[Music]

John: Thanks for joining us for Tea for Teaching, an informal discussion of innovative and effective practices in teaching and learning.

Rebecca: This podcast series is hosted by John Kane, an economist…

John: …and Rebecca Mushtare, a graphic designer.

Rebecca: Together we run the Center for Excellence in Learning and Teaching at the State University of New York at Oswego.

[Music]

Rebecca: Our guest today is Dr. Rolin Moe, the Director of Academic Innovation and an Assistant Professor at Seattle Pacific University. Welcome, Rolin.

Rolin: Thanks for having me.

John: We’re glad to have you here. Our teas today are…Rolin, are you drinking tea?

Rolin: I am John.

Rebecca: Yes!

Rolin: I am having the Maui Up Country blend that I picked up on a on a vacation that I had brought for the office, and we ran out. So I am drinking the wonderful Keurig inspired Celestial green tea today. But I am joining you guys over there. [LAUGHTER] What are you guys having?

Rebecca: I think it’s a green tea day. I’m having black raspberry green tea.

John: …and I have a ginger peach green tea.

Rolin: Excellent.

Rebecca: We’re all in sync without planning, so that’s nice.

John: We invited you here to talk a little bit about your April 2017 EDUCAUSE Review article (which has created a little bit of a stir) where you were talking about the growth of educational technology in higher ed. What types of EdTech in particular were you talking about?

Rolin: So, John that’s a good question… and a little bit of preface on the article itself. I wrote that with George Veletsianos, who is Canada Research Chair in Innovation and a Professor of Education and Innovation at Royal Roads University in British Columbia. We started this project in 2013 at a time when MOOCs had just come into conceptualization. Laura Pappano noted that the year before had been the “Year of the MOOC.” John Hennessy at Stanford said that the MOOCs were going to be a “tsunami that was going to wash away higher education as we knew it.” Clay Shirky compared higher education to a rotting tree that was in need of a lightning strike and this was going to change it… and so, this very optimistic (to the point of Pollyanna) thought on educational technology. And George and I both, as people who are scholars and practitioners in educational technology, were a little taken aback by this. The promises that were being related to educational technology didn’t match the literature. The history of educational technology didn’t match the present and the future track of these innovations, based on their previous experiences (kind of Silicon Valley startups) was not a positive one. As I mentioned, we started writing this in 2013 and the landscape kept changing. Ownership would change, or business models would pivot, and we had to rethink what we were doing. So we kind of, instead, came back to this more systematic review of what is educational technology, or EdTech, and we thought of it in socio-cultural terms as a phenomenon. So, thinking about that, it’s not necessarily a product that we are providing critique for but it’s more of the idea that by bringing products in, whether they be cloud based softwares, learning management systems, apps, learning technologies interoperability, or LTI, or outsourcing it to a third-party vendor, whatever that vendor may be. That approach cannot be thought of as altruistic in and of itself, but it is built in society that is usually, at best, tangential to education, but often completely separate… being brought in for profit bearing reasons, whereas our institutions, by and large, are education-bearing institutions that are looking to gain enough profit to continue operation. So, what EdTech are we looking at? We really want to be creating a more critical consumer of all EdTech. And you can definitely see that today in privacy issues that are coming out with Facebook and algorithmic issues that are happening with Twitter, and discussions of what constitutes free speech or hate speech on these platforms. When we wrote, we were much more thinking about the technology that’s getting into schools, but even there, some of the things that are happening in K-12: the data from these students is not necessarily protected, whether it’s getting hacked and sold to other places or if the companies themselves have connections to other products and other vendors. So, it’s a really meta piece to be thinking about. I don’t necessarily have an axe to grind with any particular software. That’s why we were very software agnostic when we were writing the piece. We just really want to be much more conscious of how we’re using technology in our teaching practice and what is happening because of the technology we’re bringing into our classrooms.

Rebecca: Thanks for laying down that groundwork. I think that foundation is gonna give us a good ground for discussion today and will help our listeners know exactly where we’re starting.

John: A lot of these things, where people were really optimistic about the introduction of MOOCs and so forth, we’ve seen all this before. Television was going to do the same thing. Before that radio was, if we go back further, printed books were going to have this big impact. So, these are issues that have been around for a long time. But, you focus on several issues that, perhaps, are more pressing now. One of the things you talked a little bit about is how colleges have been pressured by economic circumstances, by rising tuition costs and pressure to keep costs lower, to rely more on these external vendors. Could you talk a little bit more about that aspect?

Rolin: Absolutely. I need to preface here again, John, I appreciate you bringing up television. Because there’s a time that a lot of institutions invested in broadcast studios, with the idea being that we were going to be able to amplify education and we’re going to be able to have closed-circuit educational opportunities at senior centers and satellite campuses. And so you have in many land-grant colleges these forgotten studios, that in some cases are now being turned into teaching and learning centers where you have a green screen and you can show what you’re doing in Canvas, or Desire to Learn, or Blackboard, or whatever the system is that you may use… Moodle, I don’t want to leave anybody out. But, to think about my experience as an educator, I have a connection to this particular podcast. I cut my teeth as an educator in my first career, which was in film, at Duke University’s Talent Identification Program where I got to know John Kane, who has been kind of very foundational in how I think about teaching and learning. So John, thank you for that, and it’s wonderful to be on your show. We’ve seen all of this before and we failed to learn our lessons in education. So, we didn’t get out of television what we thought… what we thought we’d get out of radio we didn’t get. It’s important to look back and see “Well, what didn’t happen that we expected to happen? What did we plan for? What was the consequence? What were the unintended benefits? and what were the unintended pitfalls?” The problem, or the big difference today, is a lot of the technology is being looked at from an efficiency standpoint. So, television and radio and even if you go back, like you mentioned with the printed books, you go back to correspondence courses and using the Penny Post in order to be able to give keyboarding instruction for secretarial jobs. So, those technologies were based on much more inclusivity in education. You had a technology that made education available for more, and you had an opportunity to get away from geographic distance as what was keeping people from school. With digital technology what we’re seeing now is almost an inverse relationship that “Yes, we have this opportunity and we sell it.” So, the MOOCs were sold as an opportunity to democratize education for everybody. But, this is really framed in a cost-cutting perspective. That we’re going to bring in technology to keep costs down. That’s very important, costs in education, and higher education especially have skyrocketed, and to think about how we can be looking at this. But it’s disingenuous to say that our digital technologies are going to democratize education for all when we want to use them to save money more so than grant access. We have to look at both critically. We have to put the same research behind both. Moreover, what’s happening when our use of technology is in the gaining of data analytics that could be used, at best, in our spaces, but at worst by third-party vendors that we’ve signed contracts with that we don’t truly understand where they’re going or where they’re taking these things. So, I started with your question and went in a lot of different directions I’m realizing. But, I think it’s important to do that historical review and think about all those places because there’s a desire there, with what education’s supposed to be, if you want to think about Enlightenment-based thinking on education. But, we are at a different point now than we were with what someone like Soren Nipper would have called generations of technology. The first generation being radio, the second television, the third digital. This fourth kind, of web 2.0, has a much greater economic impact, both on the institutions as well as the whole purpose of education. That’s something that we don’t see a lot of in the literature and something that compelled George and I to write this article.

Rebecca: I’m hearing you talk about the the desire for more access but then also these rising costs. If we’re using EdTech, are students actually just getting more access? or are we just making things more expensive at the cost of actual learning?

Rolin: Yes. [LAUGHTER] It’s difficult because in some cases there is an upcharge on taking the course online. And there’s good reason for that because in order to teach a course online, if I’m an administrator, I now have to think about a faculty member who’s going to be working through that course. I have to think about any licensing that I need for contents. So, making sure that my reserves in the library can be easily flown into my LMS and that I have the rights for reproduction in that space. I have to think about instructional design, I have to think about information technology. I have this much larger infrastructure that’s involved, depending on what I’m doing: if I’m going to be using an anti-plagiarism software; if I’m going to be using an online proctoring software, a special grader, a video library of contents. There are four or five different buckets of LTI and those are the general ones, not anything discipline-specific. So, that brings this cost up. At the same time, if you think about Moore’s law, and as technology is increasing and the capacity to do things continues to increase, traditionally we have seen costs go down in this model. That hasn’t happened with education. So you have a space where students are presented in media and, I would say in a lot of cases by schools themselves, that this online efficiency opportunity to engage is going to bring your cost down, but then your cost is becoming more, because the cost on the institution is more. All of that is to say, at some point, if you’re gonna be selling both cost savings and access, that’s not a recipe for success. In many cases, we have the access, but it’s not to people, it’s not to a high impact educational experience that you have come to think with a stereotypical higher education space. I think of the Sally Struthers ITT Tech, you know, where you can do the courses in your pajamas. So we’re giving access in real time to curriculum and to materials, are we necessarily giving it to really engaging learning activities? In some cases, yes… but I don’t think the literature would say that those brightest cases of access are meeting that romanticized version of what it means to be a student in higher education. In many cases the most successful institutions in creating access and bringing costs down are the ones where faculty have been replaced by kind of quasi-administrators who work as admissions support specialists, tutors, retention specialists, program developers, and fundraisers. Kind of doing all of that from an office space, and that looks remarkably different from what we see in cinema, as somebody who works in film studies… what we see in cinema as that college experience. So, we’re gonna have to rectify what it is we think college is supposed to be with what it is we’re selling it as.

John: Might some of that be that, with new technologies… giving an example from economics… when steam engines were first introduced, we didn’t see any real improvements in productivity for decades after that. When the internet was first introduced and people shifted businesses to that, it’s taken decades before we’ve seen much of an increase in productivity. Is part of it that we try to use the new tools in the same way that we traditionally taught and we haven’t learned how to use it more efficiently, or is it something inherent in the shift to more digital media that limits the interaction between the instructor and student and may limit learning somehow.

Rolin: John, thank you for bringing that point up. If you think about professional development technology, the stereotypical overhead projector that is used to present material is then replaced by the PowerPoint…and what was interesting is, in some cases, the first uses of PowerPoint in classrooms (because of bandwidth issues) were printouts of PowerPoint slides that were then put onto overhead transparency. So what we see in many cases today what constitutes online learning is the lecture based approach the “sage-on-the-stage” model of teaching where we’re using our learning management system to do what we’ve traditionally done, and it’s what I would call a mediocre middle. It both misses the point of improving education and also misses the point of utilizing the technology, but it’s what we do. My fear is that there has been a financial success in doing things in this way, or at least creating a media culture that equates formal education to the lecture. So you think about a TED talk, or you think about a Coursera lecture… this idea that it is a faculty members responsibility to share their wisdom as the person who’s speaking through it. A podcast is another space, we’re people who are talking in a space. Now that doesn’t mean there’s not a space for podcasts and there’s not a space for lecture, but it’s easy to package that content and put it into a learning space that you’re hoping to monetize. For learning to be effective online and bring down costs, probably requires a pretty seismic shift in how we think about business as normal. Some of the early critiques of online education were that it would turn us into a fordist space, where it was gonna be the assembly line production. That was gonna get away from a faculty member as kind of an auteur, somebody who has the course from its implementation to its full assessment. With online that’s almost impossible to do for the sanity of anybody. So, in some cases, that model is going to need to change in order to be successful. We haven’t figured out what that looks like yet and the human capital costs of doing it right so far outweigh the benefits that you get from allowing students to be able to take classes from a distance and increasing your enrollment, hopefully through online. We haven’t figured out how to weigh the human labor that goes into that. And I think some of it is also we haven’t changed… I’m gonna get radical here, the expectation of what it means to be a professor is still the same as it was 50, 60 years ago, but what we consider is knowledge has changed pretty significantly with Ernest Boyer’s thoughts on scholarship. What it expects to be a faculty member… so the expectations of teaching at even teaching heavy institutions have gone up but the expectations on scholarship or service have not changed. So instead of it being a triangle of scholarship teaching and service it’s this odd triangle that is morphed into a parallelogram with no extra time given to these spaces. So, we’re gonna have to think about our governance structures and our infrastructure if we’re going to be successful. There’s an article in The New York Times this week we’re recording this in mid-September talking about what the next financial bubble may be, and it points to student loans that the cost of education has gone up fourfold over the last 30 years, outpacing everything, including healthcare… and the student loan debt has over the last five years, overtaking credit card debt. It’s the largest amount of debt that exists in any industry. That cannot keep up. Y et costs continue to rise. So another thing; in the next 7 years, that traditional college age, students 18 to 22, is going to decrease in 2025 because of demographic shifts. So, there’s a lot that’s going on at this point, and John, you mentioned the steam engine and how it took decades… Well, we keep saying we’re the Wild West and we only have years until we get to the cliff, and many people would say we’re already past that point; we’re at the point of no return. I like to be a little more optimistic than that.

Rebecca: I’m gonna go back to a little bit of discussion about access. Some of the things that I hear you describing is that the technology is allowing us to have access to information or the distribution of information. Which is why the lectures, the podcasts, et cetera are easy to package and deliver the access to that information. But, what I’m not hearing is access to learning or the access to becoming a scholar, or a way of thinking or being in the world. And I wonder if some of the movements in OER or the open education resources are trying to push the envelope or push the technology and access more in that direction, or if it’s really still emphasizing the ability to just deliver information.

Rolin: Rebecca, you bring up a really great point. And I’ll touch on OER because it’s a fascinating case study in this space, but if you look at the history of distance education with technology, the focus was on bringing people together… that the content operability was not the key point… but it was being able to bring people from disparate geographies or cultures or climates together to learn. And so it is based in constructivism and constructionism and social learning theory and activity theory and all of the wonderful progressive learning theory that is moving teaching and learning today. And the technology that is predominantly used stands much more didactic, maybe behaviorist, in approach because it’s easier to measure that than it is to measure the much more engaging work that happens when you bring people together. So I had an opportunity (I’ll try and not give away any disclosing information on this), but I had an opportunity to work with a group on a MOOC in after the first wave of MOOCs—this was 2013–2014. They were on a major platform and they had created a course, and it was not a traditional STEM course; this was an arts-based course that they had created. And the platform came to them at the end and said, here’s what happened in your class and had this ream of analytics and they said “Well, wait a second. We had a Facebook group, we had meetups, we had a lot of people create artifacts. Where does that fit into this?” And the platform just kind of shrugged their shoulders and said, I don’t know. We can tell you how long someone watched the video and they were saying, “That’s not what’s important to us. What’s important is what were the conversations that were happening and how is that gonna relate to where they’re going further.” We’re in a time of measurement today, yet our measurement structures are much more basic than our capabilities with technology. And so we’re engineering the technology to perfect those measurement techniques. We can’t do much more with bringing people together and engaging more progressive emergent learning theory with technology. I think what George and I were arguing is the technology, as it stands today, doesn’t feed that because that’s not what’s getting the clicks, that’s not what’s moving the needle, whatever metaphor that you want to use in that space. MOOCs are a fascinating space to look at this because the MOOC acronym actually comes from an experiment in social connectivist learning from 2008 with George Siemens, Stephen Downes, Dave Cormier and the great Canadian contingent. And then Sebastian Thrun didn’t even talk about it when he became the father of the MOOC in 2011. He was looking at a bold experiment in distributed learning at Stanford. It was a New York Times reporter Tamar Lewin who made the link between what George Siemens had done and what Sebastian Thrun had done and called it a MOOC. And it kind of stuck and that’s where we went with that. So it’s very interesting to look at the hype versus the research and why the hype is what’s pushing the cart when in academia we like to say it’s the research that does. Now you mentioned OER. I want to focus on that because this is a really fascinating space that in the last couple years you’ve seen this remarkable push on open educational resources, open textbooks, and I am a longtime advocate of open education… been attending the open ed conferences that David Wiley has been putting on since 2013. I ran the unconference there last year. So I’m advocate for what they’re doing. But it is interesting to think about their success and what their advertising is. Their paramount success is really focused in textbooks. So while you have the opportunity to edit a textbook and you have the opportunity for a faculty member to build artifacts of knowledge with students and cross collaboration, that’s not what’s moving the conversation today. What’s moving the conversation are these static textbooks that bring costs down for students. And I like to be the voice that’s saying, don’t forget about these places, because I worry that we’ll see something, and you can even see a little bit of it happening now with publishers who are wanting to open wash or green wash or astroturf what open is and say, “Oh, you know, here we are over here at Pearson or McGraw Hill and this is our contribution to the space.” When you look under the hood it looks remarkably different, but if the focus remains on this static text book in that adoption, it’s easy for that to co-opt. So, to answer the question in a more broad sense, I think in general we have research that’s telling us one thing and we have marketing and public relations and cultural ideology that’s saying something else. I don’t want to say we’ve done a poor job, but the two are very incongruent right now and usually it’s that media PR machine that’s pushing things and we’re playing catch-up and it’s easy to lose track of the research in that.

Rebecca: As a public institution like we are, obviously access as in all people should have access to the information is really important, but I always get concerned about the people who are generating the technology pushing it in the wrong direction and people who value everybody having education and learning not being able to push the envelope or push the technology in the direction that we want to push it in. They’re kind of butting heads in some ways.

Rolin: I would absolutely agree with that. And accessibility, it’s really wonderful to see accessibility being brought forward in terms not only of contents but also of learners, and so the stigmatism of having learning disability or an emotional or physical or some need to engage with content, that now is going to be supplemented by an institution. And that we are designing with that in mind. We’re designing a universal access and UDL that we’re engaging in this space, and that’s a really wonderful change that has happened in higher education. When people talk about the cost of higher education, it’s important to note that things like that are bringing the cost up, and I don’t think any of us would want to get rid of any of those pieces. The problem, of course, becomes “What is the historical understanding of this place?” and “What is our institutional objective and our institutional memory versus these changes that are happening in how we think about teaching and learning?” And I’ve done as much as I can locally at Seattle Pacific University to start conversations and meet people where they are and I think we’ve had some some pretty remarkable success in rethinking some of our structures, but we’re a private liberal arts institution not dealing with the state bureaucracies, not dealing with a state system, not dealing with tens of thousands of students, and it becomes difficult to navigate all of that. Bureaucracy is the least worst tool that we have in order to work with that. But it’s also a great straw man or easy fall guy for any problems that come up, and too often problems continue to exist rather than being tackled because it’s tough to think about what the benefit would be going forward.

John: In your article, you talked a bit about the increasing reliance on private vendors, outsourcing tasks from institutions to vendors on the grounds that that opens things up to the free market in some way, but when we look at the provision of most of these platforms, it’s a fairly unstable market. We’re seeing so much concentration in the market where many small publishers have disappeared, and many of the innovative educational technology providers have been bought up by other large firms. We’ve seen many providers disappear.

Rolin: I’m glad you bring that up, John, because if you think back… and John, you and I have a background in K-12 and it’s really fascinating to think about this from a K-12 perspective because in the 60s and 70s, the heyday of educational film, it was the job of the media resource specialists at a K-12 library to work with faculty to be able to understand how these pieces fit together, and so they were working with Encyclopedia Britannica and World Book and Disney and ABC and NBC and the different content providers of the time, who were making educational titles. It’s a fascinating, fascinating time. The computing craze in the 1980s came at the same time as a recession. And the idea being for people to think about how this was all going to fit together. When this was created the idea was that that role was going to be vital, and the change that happened was we got rid of the media resource specialist and believed it will be up to institutions and collaborations to grow this, to make this go further. Educational film died because it became less expensive to make it and the belief was more and more people would make it. What we instead make are lectures and YouTube videos, and there’s value to both but the great expectation that we had on what these contents could be is gone and we’ve lost that. And so there’s an opportunity… I think that if you think about learning as this contextualized and locally defined space… there’s an opportunity to be able to create these contents. But there’s a lot of risk that goes into that. There’s a lot of quality control that we we didn’t necessarily expect. And there are a lot of other costs that came in and so we output to these third-party vendors, hoping that we hit pay dirt with somebody. In many cases those companies are folding regularly or they’re being absorbed into others, the learning management system ANGEL, which was a rather popular system in the early 2000s and early part of this decade got bought out by Blackboard, and a lot of the people who liked ANGEL liked it for the reasons that it wasn’t Blackboard. But to think about, in that perspective, it’s almost impossible today for institutions to take this on their own. There’s just not a return on investment that works for that, so that means you either have to create these partnerships across institutions that historically have been at war with one another, or you invest in the promises of third-party vendor, either a small one that’s telling you what you want but may not be around in a month, or a large one that you have a lot of trust issues… best-case scenario, trust issues on the kind of service you’re going to receive; worst-case scenario, what does it look like what’s happening to your data, what’s happening to your analytics, what’s happening to the ownership of what you’re producing.

John: Going back to ANGEL a little bit, we used to use ANGEL here and in many ways I loved it; it had some really nice features that Blackboard is a ways away from getting. It had automated agents and so forth, but ANGEL was actually created at Indiana University. And one of the problems they had was that in the 2007 recession, state support for Indiana University was cut significantly and they owned this big cash cow that they could sell off… and so we lost a fairly viable provider in large part because we see in general a decline in federal and state support for higher ed and it puts institutions in a difficult bind where they often outsource more and more.

Rolin: Absolutely and ANGEL is a good example of that. You can go into the 60s with Plato. It was a Midwest State school that was doing Plato. I think about Quest Atlantis was another great thing that gets mentioned in all sorts of progressive educational research that was funded by grants and the funding dried up and there was no way to sustain it. The MEK Corporation, the people who created Oregon Trail and super munchers and that educational software, where is that today? And I work in educational film, I think about it from that perspective. How have we lost those film providers and now we just think that content will fit in for what was historically this really rich and vibrant place to engage, but we’ve lost it on the software side and the teaching and learning side, and we’re outsourcing so much of what we already do to the free market. Certainly there is benefit to that, but at what cost? And I don’t think there’s been enough analysis of what that cost has been.

Rebecca: So, you’re really bringing up the idea that EdTech is not neutral and that there’s competing goals. So, technology companies are obviously trying to make money and then we’re trying to have students learn, ideally. How do we help those things become more aligned? What needs to happen so that we’re not at odds but that we actually find alignment and essentially make the world better which, in theory or in PR, is what’s being said?

Rolin: I think for the first piece, Rebecca, is understanding that EdTech is not neutral, and once we have that foundation, that we understand what we’re using and what it relates to, we can be much more thoughtful about how we use it. So, I am a faculty member but I am primarily an administrator and I use our learning management system here on campus. I could go off the grid; I could try and do something completely different, but it’s important to show support of what we’re doing with an understanding of how that works, and so we have our LTI, whether it’s anti-plagiarism software or proctoring software and all these pieces, and as a scholar I can have criticism of that. So, as a practitioner, how do I help my students understand what they’re getting into with this and making informed decisions about that space. So, I think it really comes into this idea of understanding the learning environment and what my job is: to control… to create pathways for students to be able to learn and to scaffold that and to fill knowledge gaps and help people expand their zones of proximal development, to go Vygotsky on us. I need to cede some of the “management control” that goes into: “Well, we use this, and this is what’s going on.” But, let people make thoughtful decisions about what’s happening with the technology that they’re using. My son in K-12 can opt out of state standardized testing and that’s a decision that’s made as a family. Dealing with college students, we don’t give them the same rights to opt out of some of the technologies that are being used. So, I think about the proctoring technology that was out of Rutgers that was running in the background on computers using retinal scans to engage people and that’s just what you get when you sign up and there’s no informed decision or consent. There’s not even a Terms of Service that you have to read through and then click a button that you don’t actually end up reading. Can we have more of these conversations? Can we be more informed? Because, if we have that information, we’ll be much more thoughtful in the decisions we make on what vendors we choose. The vendors will then have to respond to that market in making software that is more open or more transparent in its use and the application of its data. People have to make a profit. Education has to make a profit. We can marry those pieces together and have a somewhat vibrant marketplace that is serving the learning of students. I think the issue is, right now for EdTech, the student is the customer, not the buyer, and so there’s a gap there that if we have students much more involved in all aspects of that and involved in those conversations, that becomes part of learning experience. I think that that could see some more direct improvements than just generally saying, “well, we’re thinking about this and we’ll continue to think about this going forward.”

Rebecca: I think one of the things I’m sorry I was gonna pick up on the threat of audience but okay

John: You mentioned keeping students in the zone of proximal development. One concern with standard lecture based teaching is that students are pretty much forced to move along at one pace. What’s your reaction to adaptive learning? Is that something that could help, or are there some limitations that we should be concerned with there?

Rolin: I mentioned Plato earlier, the first personalized learning network—basically adaptive learning. I think that there’s a wonderful opportunity for adaptive learning platforms and for being able to bring in competency-based education into spaces. Thomas Edison University has an amazing program that is built on the idea of competency-based education. Alternative pathways and moving away from “seat time…” there’s definitely viability for that. It just has to be thoughtfully executed… and what is the purpose of the learning that is happening in that space? So, if I think about a School of Health Sciences, I think about nursing… if I’m going to get a degree in nursing, there are really specific things that I need to do. I need to pass very specific exams that are proctored in very specific ways that expect me to maneuver in very specific fashions. The seat time is important for that, and that space there needs to model what I’m going to be getting into in an industry. So, I can’t be an intrepid change agent saying, “No, this needs to be social learning theory,” it needs to be what takes off in nursing. No, nursing students need to be able to be successful in the expectations of their field. There are the places that adaptive learning can fit into that. You see it in foreign language in many cases and the supplements that are happening there. Keyboard instruction is another one where that comes in. So, how could we use the best of that to be getting into other spaces. I think some things that we could explore there, as we rethink disciplines and what works for economics or film studies or education. I think there’s some places with that critical thinking… that soft skills, 21st century learner stuff… where the adaptive learning could come in…. so, misinformation, media literacy, fake news… big hot topic and I wrote an article in 2017 that got a lot of attention (not all positive) saying that fake news wasn’t the problem; it’s not what’s ended up resulting in Brexit or the results of the 2016 election. But it was a small part of a landscape that had been neglected and was suffering from blight for a long time because of how we teach this stuff. And I wonder if thinking about digital literacy, which we’re all expected to incorporate into our classrooms, if that could be served by an adaptive learning platform that engaged content, theory, criticism and evocative video to be able to move somebody on a pathway. That’s a place where all of us could come together because there’s no discipline that owns information literacy. It’s built out of information literacy in libraries. But librarians often are the most flexible in thinking about how their craft is going to change. Places like that, critical thinking, the stuff that we’re all told needs to be imparted to our students, but it’s just kind of this hooray concept of “Oh yeah, let’s have this.” Maybe those are the places to really focus on the successes of that and then the research can help define how economics could engage adaptive learning or film studies or education or cell biology.

Rebecca: One of the things that you said earlier is that students aren’t the audience of or aren’t the buyers of the technology. And I wanted to shift that a little bit to thinking about audience and who things are designed to and I think you’re right in that tech companies are selling to administrators who are the ones that are doing the buying and the purchasing who are trying to facilitate certain things, keep cost down, et cetera. How do we shift that conversation so that tech companies start to see the end users who are really students and faculty as the audience of their marketing, of their conversations, and actually shift things so that they focus on the research around learning and improve learning rather than just facilitating something?

Rolin: The key part of what you said, Rebecca, you kept going back to learning, and I think that’s what’s missing in these vendor conversations. We have this idea of what learning is and if I’m a vendor and have mounds of data I can point to achievement and I can point to the things that I measure in my platform that lead to that achievement, and for most instructors that’s not evidence of learning. That might be a small part of it but there’s a much larger picture. And we do a poor job of amplifying that research. That research doesn’t play well in mainstream media, so how do we do a better job of sharing that research. What constitutes learning? What makes learning happen? I love going to YouTube and looking up “do-it-yourself how to fold a fitted sheet,” ‘cause I don’t do a good job of folding a fitted sheet. And I’ve tried numerous times and I still struggle, so that video isn’t the piece that I need to be able to move me there. Now, there are other pieces, potentially making something for dinner that I would be able to replicate in that space, but replication again is not learning. So, even an understanding of: What is learning? What does that mean? How do we define what it is to have learned something? What it is to be a learner? “Lifelong learner” is a commodified term at this point when it really should be a state of being for, I would say, pretty much anybody. How do we engage those conversations? That’s a really complex question. In terms of an institution, how do we bring more student voices into these spaces? and not in a placating fashion of, “Well, we now have a student sitting on this committee.” But to really understand how that student can canvass and caucus with their peers to be able to provide us information. In the same way that if I’m serving on a faculty committee so that I’m meeting my service requirements, but if I’m getting something out of that and I’m giving back that’s a wonderful experience. A student serving on a committee… how can we provide them what they need for their CV or for their graduation in a way that what we’re asking from them they can provide us? …and not just sitting there and saying we’re listening to what they’re providing but often not doing that. So, more student voices in those decision-making processes… more research that’s going to be shown to the vendors… and I think we need to be more thoughtful about those vendor conversations. One thing we do here at Seattle Pacific University, we actually have… with our faculty… we provide entry points for vendor assessment when we do test demos. What are some of the things that faculty who are very interested in being part of these conversations but are coming in the middle of it… what’s happened so far and what are questions they can ask we’ll be able to draw out their expertise and what we need from the vendor? The more of that that we do, the better. I know the California State University systems doing something similar on automating a great deal of the pre-production that goes into assessing vendors so that the stakeholders who are asked these questions have that information in a repository and can access it very easily to make an informed decision, rather than it being brought down from higher administrators… lots of information that’s tough to digest in a small period of time.

John: What do you see as some of the most promising areas where EdTech has some potential?

Rolin: Excellent. My wife loves to say it’s very easy to show why you’re against something, but you get into this business to be for something. Get in education to really share the diffusion of knowledge and help people rise to heights they didn’t know were possible. Fall in love with things they don’t yet know exist as Dr. Gary Stager would say. So, what are some of the positive things that are happening? I really think there’s a chance for a revolution in multimedia. Here’s this podcast that is happening in an interdisciplinary fashion in SUNY Oswego bringing in a faculty member from a completely different perspective who serves an administrator having this conversation. More and more of this is happening. Before we went on the air, John, you were talking about editing your two channels and making sure the sound was right and all of these skills that were picked up that don’t come when you get your PhD in economics. So, as these pieces are coming in how do we value that and so you see more administrations and more governance bodies that are providing value to that. We were talking, Rebecca, about open education. The University of British Columbia now will recognize the editing of OER materials as part of promotion, tenure, and review for their School of Education. That’s a phenomenal change that has happened in how we think about the role of the faculty member as a distributor and conveyor of knowledge. I think people are being more thoughtful at this in this day and age. But, you did ask specifically about technology, so I need to pivot back there for a second. I love some of the stuff that’s happening in virtual and augmented reality. Some of the really interesting research that’s happening there. I like the drop-in classes that are happening around special interest topics that often, in many cases, are informal or non-formal learning spaces. Museums putting on areas where you can come in and learn in a certain time. Kind of a gap between a human experience and the MOOC but you’re kind of doing both at the same time. I think that the opportunities that we have with free and ubiquitous devices… and I don’t mean free as in cost but I mean free as in access to… and especially in the West with broadband capabilities, what’s going on with video and how we can better engage that and as more people learn about nonlinear editing and cinematography and camera and sound. What are some of the resources we’re gonna build there? Opportunities for students to share their knowledge is the main thing that comes forward for me. WordPress, which runs, what, a quarter of websites in the world is getting incorporated more and more into courses. You think about the WordPress camps. There’s a great thing happening in New York City coming up on managing the web and how you can work with students to be able to be creators and owners of the knowledge that they’ve created and what the implications are in that space. It is kind of a tough time to be bullish on technology if you think about Facebook and Google and Apple and Amazon and antitrust that’s going on in all of those spaces. And so a lot of the stuff that I’ve mentioned here is somewhat renegade, somewhat guerrilla even. So where are those opportunities to engage with environments through online? It comes back to community in that space. How do you find and foster that in your networked identity. There are opportunities and more and more that’s going to be happening. I think that we’re in this storm and after this there will be, not a calm, but there will be an opportunity to look at what’s been broken and how can we build and improve going forward, and I think that we’re getting to that point sooner rather than later.

Rebecca: We generally wrap up by asking what’s next. You talked a little bit about what’s next in EdTech, but what’s next for you?

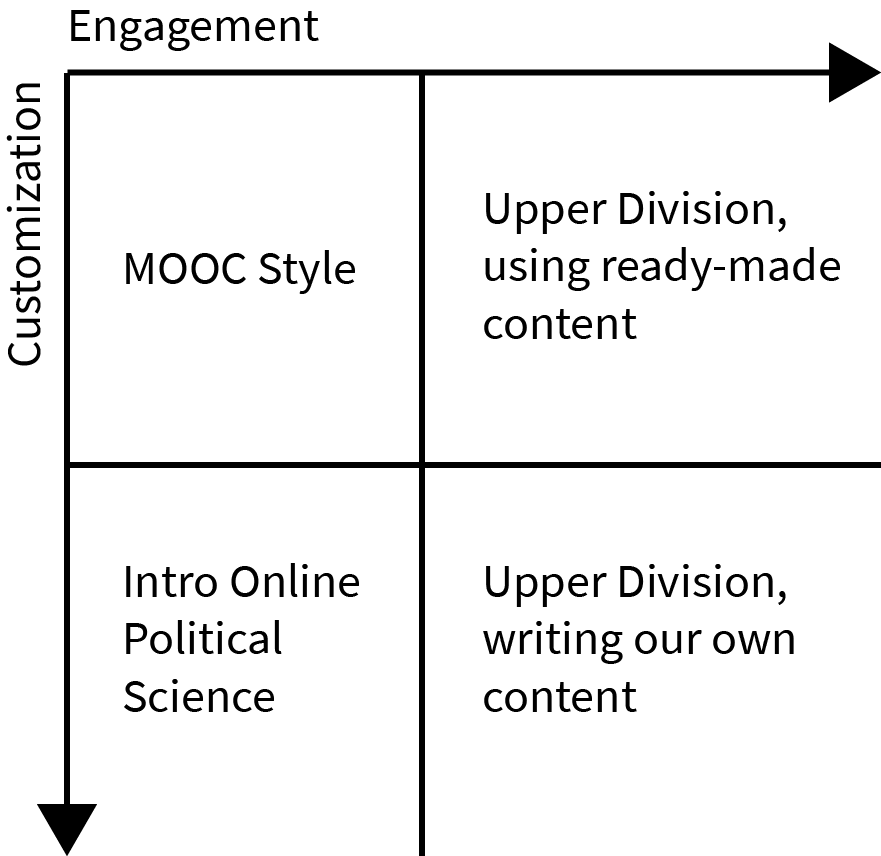

Rolin: What we’re doing at Seattle Pacific University around academic innovation; we have been offering seed grants to faculty for the innovations that they see as necessary, whether that’s in a classroom, in a department, in a college across the entire campus working out in the community. We provided 45 of those over a two-year period, so almost a third of our faculty directly affected by those and it was very powerful, so we’re taking that a step further and engaging at a school or college level and finding innovations that we can then potentially put into day-to-day operations. So, one of the things we’re thinking about actually are adaptive courses. What would it look like for a course in nonlinear video editing to be almost entirely online. And you think about that with lynda.com. I can go to lynda.com and take a tutorial in using Final Cut or Adobe Premiere. What am I getting out of being in a higher education institution that I can’t get off of Lynda? That’s what we’re exploring: what does it look like to have that scaffolding and support that’s directed toward a greater understanding of knowledge? Other things are definitely around social justice. We are seeing at Seattle Pacific an increase in first-generation and historically underrepresented students who are coming in with the same scores as their peers but, once they get here, we’re seeing a discrepancy between where we would expect them to score and where they are scoring. And we have statistically significant research showing that that is the first-generation student demographic. So, what are some pieces we can put into play to be able to help them with their success? Because it’s not a matter of not being able to do it; it’s a matter of the structure and the culture is not befitting them. So, we have a program called the Bio Core Scholars where we are working with tutoring and mentorship on research, community, and knowledge gaps to be able to move these students. We’re in our fifth year of this program, we’re looking at expanding it. But we have brought the students up a full standard deviation in their scores, and we had an 86 percent success rate in graduating people to pre-professional health programs, which is just a remarkable number. Personally, I’m really big on what we can do with educational video. What are some of the things instead of it just being a lecture? I love Skunk Bear on NPR, taking a topic and in three minutes doing an entertaining, evocative dive into that topic, but again, that’s Oliver Gaycken would call “decontextualized curiosity.” How do we take that and actually put it towards learning? So, I’m looking at what does it look like to have lecture mixed with a very product based assessment mixed with more evocative filmmaking to move people into learning? How does that all go forward? It’s a very exciting time to be in higher education, even with all of the things that are looming on the horizon.

Rebecca: Certainly doesn’t sound like you’re gonna be bored any time soon.

Rolin: Not at all.

John: Thank you for joining us. We look forward to hearing more about this.

Rolin: John, Rebecca, thank you guys for having me.

Rebecca: Thank you.

[MUSIC]

John: If you’ve enjoyed this podcast, please subscribe and leave a review on iTunes or your favorite podcast service. To continue the conversation, join us on our Tea for Teaching Facebook page.

Rebecca: You can find show notes, transcripts, and other materials on teaforteaching.com. Theme music by Michael Gary Brewer.