A year ago, our campus announced that it was shutting down for a two-week pause so that the COVID-19 pandemic could be brought under control. To help faculty prepare for remote instruction, we released our first episode of many on March 19, 2020, with Flower Darby. We thought this would be a good moment to pause and reflect on this journey.

Show Notes

- Flower Darby (2020). “Pandemic Related Remote Learning.” Tea for Teaching Podcast. Episode 126. March 19.

- Todd, E. M., Watts, L. L., Mulhearn, T. J., Torrence, B. S., Turner, M. R., Connelly, S., & Mumford, M. D. (2017). A meta-analytic comparison of face-to-face and online delivery in ethics instruction: the case for a hybrid approach. Science and Engineering Ethics, 23(6), 1719-1754.

- Means, B., Toyama, Y., Murphy, R., Bakia, M., & Jones, K. (2009). Evaluation of evidence-based practices in online learning: A meta-analysis and review of online learning studies.

- Lang, J. M. (2020). Distracted: Why Students Can’t Focus and What You Can Do about It. Basic Books.

- Linda Nilson (2019). “Specifications Grading.” Tea for Teaching Podcast. Episode 86. August 21.

- Susan Blum (2020). “Peagogies of Care: Upgrading.” Tea for Teaching Podcast. Episode 145. July 22.

Transcript

Rebecca: A year ago, our campus announced that it was shutting down for a two-week pause so that the COVID-19 pandemic could be brought under control. To help faculty prepare for remote instruction, we released our first episode of many on March 19, 2020, with Flower Darby We thought this would be a good moment to pause and reflect on this journey.

[MUSIC]

John: Thanks for joining us for Tea for Teaching, an informal discussion of innovative and effective practices in teaching and learning.

Rebecca: This podcast series is hosted by John Kane, an economist…

John: …and Rebecca Mushtare, a graphic designer.

Rebecca: Together, we run the Center for Excellence in Learning and Teaching at the State University of New York at Oswego.

[MUSIC]

John: Our teas today are:

Rebecca: I’m drinking English Afternoon for the first time in about a year. Because I’ve been home, and working from home, I’ve been drinking pots of loose leaf tea instead of bag teas. And so I’m bringing back the comfort of a year ago.

John: And we still have in the office several boxes of English A fternoon tea, but they are wrapped in plastic. So I’m hoping they’ll still be in good shape when we finally get back there …once this two week pause that we started about a year ago, ends.

Rebecca: Yeah, when we recorded that Flower Darby episode was the last time we saw each other in person.

John: Well, there was one other time…

Rebecca: Oh, when you dropped off equipment.

John: I dropped off a microphone and a mixer for you so that we could continue with this podcast. Actually, I think we saw each other from a distance because I left it on the porch because I had just come back from Long Island where infection rates were very high.

Rebecca: Are you drinking tea, John?

John: …and I am drinking Tea Forte black currant tea today.

Rebecca: A good favorite. So John, can you talk a little bit about where you were at mentally and just even conceptually, in terms of online teaching and things,when the pandemic started a year ago,

John: We were starting to hear about some school closings in other countries and in some cities in the US where COVID infection rates were starting to pick up and it started to look more and more likely that we’d be moving into a shutdown, in the week before we were to go to spring break. I was teaching at the time one fully asynchronous online class and two face-to-face classes. When it was looking more and more like we’d shut down I talked to my face-to-face classes about what options we’d have should we go online for some period of time. And I shared with them how we could use Zoom for this. And we had already used Zoom a few times for student presentations when students were out sick or had car trouble and couldn’t make it into class. Because they were actively using computers or mobile devices every day in class, anyway, they all had either computers or smartphones with them. And I had them download Zoom and test it out, asking them to mute their mics. And very quickly, they learned why I asked them to do that. I wasn’t very concerned because we’ve been doing workshops at our teaching center for many years now with remote participants. And we’ve been using Zoom for at least five years or so now. So I wasn’t really that concerned about the possibilities for this. And I thought the online class would go very much like it had and the face-to-face classes would work in a very similar way… for the short period that we were expecting to be shut down. I think even at the time, many of us thought that this would be somewhat longer, but I wasn’t terribly concerned at the time, because infection rates were still pretty low. And I think we were all hopeful that this would be a short-run experience.

Rebecca: And also maybe the fact that you’ve taught online before didn’t hurt.

John: Yeah, I’ve been teaching online since 1997, I believe. And so I was pretty comfortable with that and I wasn’t concerned at all about the fully online class, I was a little more concerned about the students who were used to the face-to-face experience adapting to a Zoom environment.

Rebecca: I had a really different experience because I was on sabbatical in the spring working on some research projects related to accessibility. Because of that, I was able to quickly adapt and be able to help some communities that I’m a part of, related to professional development. So I stepped in and helped a little bit with our center and did a couple workshops and helped on a couple of days with that. And I also helped with our SUNY-wide training too, and offered some workshops related to accessibility and inclusive teaching at that time. And the professional association for design locally, we had a couple of little support groups for design faculty.

John: I wasn’t too concerned about my classes, but I was a little bit more concerned about all the faculty that we had who had never taught online. And so, as you just said, we put together a series of workshops for about a week and a half over our spring break helping faculty to get ready for the transition to what we’re now calling remote instruction.

Rebecca: At that time, too. I had no experience teaching online, I’d used Blackboard and things like that before, but not to fully teach online. So for me, it was a really different experience. And I was helping and coaching faculty through some of those transitions too, not really having had much experience myself. So I had the benefit, perhaps, of seeing where people stumbled before I had to teach in the fall. But I also didn’t get any practice prior to fall like some people did with some forgiveness factors built into the emergency nature of the spring.

John: I think for most faculty, it was a very rapid learning process in the spring and instruction wasn’t quite at the level I think anyone was used to, but I think institutions throughout the country were encouraging faculty to do the best that they could, knowing that this was an emergency situation, and I’m amazed at how quickly faculty adapted to this environment overall.

Rebecca: One of the things that I thought was gonna be really interesting to ask you about today, John, was about online instruction, because you have such a rich history teaching online, and there are so many new faculty teaching online, although in a different format than perhaps online education research talks about. Many people taught asynchronously for the first time, but there’s also a lot of faculty teaching online in a synchronous fashion. There’s a lot less research around that. How do you see this experience impacting online education long term.

John: I don’t think this is going to have much of a dramatic impact on asynchronous online instruction in the long term. Online instruction is not new, it’s been going on for several decades now. There’s a very large body of literature on what works effectively in online instruction. And under normal circumstances, when students are online and faculty are online because they choose to be, online instruction works really well. And there’s a lot of research that suggests that when asynchronous courses are well designed, building on what we know about effective online teaching strategies, they’re just as effective as well designed face-to-face classes. However, a lot of people are trying to draw lessons from what we’re observing today. And what we’re observing today, for the most part, does not resemble what online education normally is, primarily because the students who are there, and many faculty who are there, are there not by choice, but by necessity. And one of the things that has come up in some recent Twitter conversations, as well as conversations that we’ve had earlier, is that many online students in asynchronous classes have been asking for synchronous meetings. In several decades of teaching online, I’ve never seen that happen before, and now it’s very routine. And I think a lot of the issue there is that, in the past, most online students were there for very specific reasons. So they may have had work schedules that would not allow them to sign up for synchronous classes. Some of them are in shift work, some of them were on rotating shifts where they couldn’t have fixed times of availability. Some of them would have large distances to commute and it just wasn’t feasible, or they were taking care of family members who were ill, or as part of their job, they were required to travel. In most of the online classes I’ve had in the past, there were some students who were out of state or out of the country. I had students during the Gulf War who were on a ship, the only time they missed a deadline was when their ship went on radio silence before some of the attacks down there. They simply would not have been able to participate in synchronous instruction in any way. And I think a lot of the people who are now taking asynchronous classes, strongly prefer a synchronous modality and are disappointed that they’re not in that. And I think a lot of what we’re seeing is a response to that and I think we shouldn’t ignore all the research that has come out about effective online techniques in light of the current pandemic, because this is not how online instruction normally has occurred. And people are in very different circumstances now in terms of their physical wellbeing in terms of their emotional well being and just general stress.

Rebecca: Yeah, during the pandemic, many more people are in isolation, and might really be craving some of that social interaction that they might not expect out of an online class traditionally, especially if it’s an asynchronous class. But if you’re just alone, and you’re not going out of your house, there might be more of a desire during this one moment of time …this one really long moment of time. [LAUGHTER]

John: During this two-week pause? [LAUGHTER]

Rebecca: Yeah. One other thing, I guess, is important to note as we’re talking about research and what evidence shows is that hybrid can be really effective with the combination of in-person instruction complementing some asynchronous online instruction. And of course, in that traditional research, hybrid really means this in- person and then asynchronous online, this synchronous online thing wasn’t really a thing prior to the pandemic. [LAUGHTER]

John: Right. And we can’t really draw too many conclusions about this giant worldwide experiment that’s being done in less than optimal conditions without really having a control of normal instruction to compare it to. And yeah, several meta-analyses have found that while face-to-face and asynchronous online instruction are equally effective, hybrid instruction often has come out ahead in terms of the learning gains that students have experienced. Certainly, we know a lot about hybrid instruction, face-to-face instruction, and asynchronous online, but not the modality that larger of our students are in. One other factor is that when people signed up for online classes before, they did it knowing that they had solid internet connections, they knew they had computers that were capable of supporting online instructional environments. They had good bandwidth and so forth. That’s not the situation In which many of our students and faculty are working right now, because faculty and students often do not have any of those things. And they’re often working in suboptimal environments that are crowded, where there’s other people in the household sharing the same space. And it makes it really difficult to engage in remote asynchronous or synchronous work as they might have when they chose to be in that modality.

Rebecca: I do think that, during this time, though, into kind of forced online instruction, although there are certainly people who don’t like that they’ve been forced to be online, and they prefer to be synchronous or in person, I think there’s a cohort of people who thought online education wasn’t for them, both faculty and students, who have discovered that it actually really does work for them. And even me, although I teach web design and do things online, you’d think online education would seem obvious to me. But in the past, it hadn’t really occurred to me. Our education tends to be in person, and you tend to replicate what you’ve experienced. [LAUGHTER] And although I have taken some online courses related to design and technology and coding in the past, it hadn’t really occurred to me to consider some options. And I think what we’ve discovered is some of our courses work well in this modality and some don’t. Some of our courses are better positioned to be potentially online or work well in that format, and could help with some collaboration pieces, or some other things that we might be doing. It might support the work that we were already trying to do in person.

John: And I think now, all faculty have gotten much more comfortable with a wider variety of teaching techniques and teaching tools than they would have experienced before. For many faculty, just having dropboxes in the learning management system was something new, moving away from paper assignments was something very new. And suddenly, faculty were asked to use a wide variety of instructional tools that they had been very careful to avoid doing in the past. And one of the things that struck me is how many of the people in our workshops who’ve said that they were perfectly comfortable teaching in a face-to-face environment, and they just didn’t see the need for, or they didn’t think that online instruction could work for them. And now that they’ve tried all these new tools and these new approaches, they’re never going to go back to the traditional way in which they were teaching. So I think there are going to be a lot of things that people have learned during this that they’ll take back into their future instruction, even if it is primarily in a face-to-face environment.

Rebecca: It may also be some changes in technology policies in the classroom as well related to just seeing how helpful technology can be for learning, but also where it can be distracting. So I think there’s some reconsideration of what that might mean.

John: While there haven’t been so many things that I’ve enjoyed during the pandemic, one of them is that this whole issue of technology bans have pretty much fallen to the wayside. I’m not hearing faculty complaining about students using computers during their class time now. And that’s a nice feature, and perhaps faculty can appreciate how mobile devices can be an effective learning tool. And yes, there will have to be more discussions such as one we’re having in our reading group this semester, where we’re reading Jim Lang’s Distracted: Why Students Can’t Focus and What We Can Do About It. There’s a lot of discussion about when technology is appropriate, and when it’s not in those meetings. But I think faculty have come to recognize how ed tech can be useful in some ways, at least in their instruction, whether it’s in person or whether it’s remote.

Rebecca: I think it’s also important to note that how some of the synchronous technology, video conferencing technology like Zoom, has some advantages, even if our class is not synchronous online. It could just be an in person class in the future. We’ve seen the power of being able to bring guests in easily without having to deal with logistics of traveling and the scheduling considerations that are often involved with that. We don’t have the disruptions and education related to snow days and illness, both on the faculty and student side. Obviously, that depends on how severe the illness is, right? [LAUGHTER] Professional development has worked out really well online, although we’ve done online or had a Zoom component where you can kind of Zoom and being all on the same platform at the same time has been really great, being able to take advantage of breakout rooms and things like that. We’ve seen record numbers attend, and then also with advisement and office hours. It can be really intimidating to have to find an advisor’s or a faculty member’s office and you have to physically go there. And then it’s kind of intimidating. What if the door’s shut? What if they’re look like they’re busy? [LAUGHTER] There’s all these things that can get in the way that online or Zoom calls can just remove some of those barriers and also allow for more flexibility because now you don’t have to plan for walking across campus which might take some time. Or you might be able to squeeze in something at a time you wouldn’t be able to otherwise.

John: And a lot of our commuting students are commuting from 30 to 60 miles away, and it was not terribly convenient for them to have to drive up to campus at a time that was convenient for their professors just for the chance of sitting there and talking to them for a few minutes. So, the access is much easier using Zoom or other remote tools.

Rebecca: We should also get real. Zoom fatigue is a real, real, thing. It’s about 4:30 right now that we’re recording. We’ve both been on Zoom calls since early this morning. And kind of constant. Our students have been as well. There’s no let up, there’s no breaks. We don’t get the little stroll across campus to the next meeting. [LAUGHTER] There’s none of that. One of the things that I am experiencing, as someone who’s definitely introverted, is this performative nature of being on camera all the time. And I know our students are too. And John and I were talking about this a little earlier today, that, in the fall, I had tons of students participating with their cameras on and their microphones on, and even in the beginning of the spring, but there’s something about the dead of winter in Oswego, that kind of Doomsday nature of it, it’s gray here. And then the black boxes just kind of emphasize it further. And they’re not as visible as they had been before. And I think it’s partly because it’s so performative, and you’re being watched all the time. And it’s not necessarily not wanting to participate or feel like you’re present. But really, it’s just a little much.

John: And neither of us pressure our students to turn their cameras on. We welcome that, we invite them to do that, but we know there are some really sound reasons not to, because people are often working in environments that they don’t want to share with their classmates or with their faculty members. And they may have bandwidth issues and so forth. But it is really tedious to be talking to those black boxes. And as Rebecca and I talked about earlier, both of us are also creating videos. So, we get to talk to our web cameras a lot, and then we go to class, and we talk to our students. Most of our students, I think, turn their microphones on. So we get to hear them one at a time. But it’s challenging to be talking to people you can’t see all day long.

Rebecca: I think it’s particularly challenging for faculty, because there’s more of an expectation for faculty to have their cameras on both in class and in meetings than students. So I think there’s an extra level of fatigue that’s happening with faculty and staff, because it’s more performance more of the time. Some days, I really feel like I wish I could be a student and I could just turn my camera off.

John: I have a night class that meets for about three hours. And typically when we met face-to-face, we’d take a 7 to 10 minute break in the middle of that. I asked the students if they wanted to do that the first two weeks, and each time they said “No.” I said, “Well, if you need to get up, use a restroom, or walk around, please do it. But what I wasn’t considering is the fact that, while they were doing that, I was still here interacting with them the whole time. And that three-hour session can be a bit challenging by the end of it, particularly if you’ve been drinking a lot of tea.

Rebecca: That’s actually important to note that, kind of unusually, John and I are both teaching three-hour classes, that’s probably not the norm for most faculty. I’m teaching studio classes. So for one class, it’s three hours of time, two times a week, and you’re teaching a seminar class, right, John, that’s three hours?

John: Yes, that meets once a week.

Rebecca: These longer sessions, we can break up by physically moving around the classroom and things when we’re in person, it becomes more of a challenge online. And I know that I’ve been thinking more about the orchestra of it all and changing it up in my classes. So we might do something in small groups then may do something as a big group, we participate in a whiteboard activity, then we might do something else, then we take a break, then we try to do something that’s off screen for a little bit and then come back. And so I’ve tried to build in some opportunities for myself as well to be able to turn my camera off at least for a few minutes during that three-hour time or take a little bit of that time during breakout sessions or whatever, because I need a break too. Our good friend Jessamyn Neuhaus has mentioned this to us many times before, that we’re not superheroes, and we should stop trying to be superheroes. And this seems like a good moment to remind ourselves of this as well. I know for me, it’s like I need a snack, I need to go to the bathroom, I need a drink. I would do that in a physical class. I take breaks then. So I’ve been making sure we build it in, and actually even padding it a little bit and giving people longer breaks than I would in person.

John: And our campus, recognizing the challenges that faculty faced with this last fall, put in two wellness days where no classes were held, and people were encouraged to engage in activities to give them that sort of break. I’m not sure about you, but I ended up spending about seven and a half hours of that day in meetings that were scheduled by various people on campus.

Rebecca: Yeah, and students also said that they ended up really needing that time to just catch up, because the workload in terms of student work hasn’t reduced, but being on screen has increased for most people, and you just need some time away. So, it ends up taking more hours of the day, just in terms of logistics, if you actually going to give your eyes a break and things. I did a little survey of my classes and they said they spent a lot of that time kind of catching up, although maybe the pace of the day was a little slower.

John: Going back to the issue of cameras being on, one of our colleagues on campus did a survey of the students in her class asking why they chose not to have their cameras on. And the response seemed to indicate that a lot of it was peer pressure, that as more and more students turn the cameras off, they became odd to leave them on. So I think many of us have experienced the gradual darkening of our screens from the fall to the spring,

Rebecca: I found that there’s some strategies to help with that as well. One of the things I did last week was invite students to participate in a whiteboard activity online indicating what they expected their peers to do so that they felt like they were engaged or part of a community. What should they do in a breakout? And what does participation look like in an online synchronous class? And they want all the things we wanted them too. They said, like, “Oh, I want people to engage.” And we talked about what that means, that it might mean participating in chat, it might mean having the cameras on, and things like that. And that day, right after that conversation, so many people during that conversation turn their cameras on. So in part, it’s about reminding, or just pointing out that it’s not very welcoming to have not even a picture up.

John: And this is something you’ve suggested in previous podcasts to that, while we’re not going to ask students to leave their cameras on to create a more inclusive environment, you could encourage students to put pictures up.

Rebecca: Yeah, we feel as humans more connected when we see human faces. So we feel much more connected than looking at black boxes. [LAUGHTER] So I’ve definitely encouraged my students. On the first day, I gave instructions to all the students about how to do that. And then when we had our conversation the other day, when I was starting to feel the darkening of the classroom and more cameras came on, I also just invited and encouraged everyone else. If you can’t have your camera on, or you have a tendency not to be able to put your camera on, that’s not a problem, but we would really welcome seeing your face or some representation of you as an image.

John: What are some of the positive takeaways faculty will take from this into the future?

Rebecca: It’s been interesting, because we’ve had far more faculty participating in professional development opportunities, initially out of complete necessity, like “I don’t know how to use Blackboard” and starting with digital tools and technologies, and then asking bigger and more complicated questions about quality instruction online as they gained some confidence in the technical skills. So there’s some competency there that I think is really great. And that’s leading to faculty wanting to use some of these tools in classes, it might mean just using Blackboard so that the assignments are there, and the due dates are more present, and just kind of some logistical things to help students keep organized. But also, there’s a lot of really great tools that, as we mentioned earlier, that faculty have discovered that they want to use in their classes. So maybe it’s polling and doing low-stakes testing in their classes during the class. I’ve discovered using these virtual whiteboards, which actually logistically work better than physical whiteboards in a lot of cases in the things that we’re doing, because everyone can see what their collaborators are doing better. So there’s a lot of tools that I think faculty are going to incorporate throughout the work that they’re doing. But also they’ve learned a lot more evidence-based practices. And maybe you want to talk a little bit about that, John,

John: At the start of the pandemic, the initial workshops, were mostly “How do I use Zoom?” But very quickly, even back in March, we also talked a little bit about how we can use evidence-based practices that build on what we know about teaching and learning. In the spring, there wasn’t much faculty could do in the last couple of months to change their courses. But we did encourage them to move from high-stakes exams to lower-stakes assessments to encourage students to engage more regularly with material, to space out their practice, and so forth. And at the start of the summer, we put together a mini workshop for faculty on how to redesign their courses for whatever was going to happen in the fall. And it was basically a course redevelopment workshop, where we focused primarily on what research shows about how we learn and how we can build our courses in ways that would foster an environment where students might learn more effectively. Our morning sessions were based primarily on pedagogy and then in the afternoon, we’d go over some sessions on how you can implement that in a remote or an asynchronous environment, giving people a choice of different ways of implementing it. By the start of the summer, people were starting to think about doing things like polling, about doing low-stakes testing, or mastery learning quizzing, and so forth. And people started to implement that in the fall. And then we had another series of workshops in January. We normally have really good participation, but we had, I believe, over 2000 attendees at sessions during our January sessions. And during those sessions, we had faculty presenting on all the things that they’d learned and how they were able to implement new teaching techniques. And it was one of the most productive set of workshops we’ve ever had here, I believe. And what really struck me is how smoothly faculty had transitioned to a remote environment. At the start of the pandemic and during spring break, we were encouraging people to attend remotely and yet faculty mostly wanted to sit in the classroom with us, and we wanted to stay as far away from those people as we could. But about half the people attended virtually. Butwhat’s been happening as people were getting more and more comfortable attending remotely and we’ve been offering the option of people attending virtually since I took over as the Director of the teaching center back in 2008, I believe. However, we rarely had more than a few people attending remotely. And it was always a challenge for people to be participating fully when they were remote while other people were in the same room, which gave us some concerns about how this was going to work in the reduced capacity classrooms that many colleges, including ours, were going to implement in the fall. And we knew we didn’t really have the microphones in the rooms that would allow remote participants to hear everyone in the room and vice versa. Once we switched entirely online, where all the participants in the workshops were in Zoom, it’s been much more effective to have everyone attending in the same way, so that we didn’t have some people participating in the classroom and others attending remotely. And I think that, combined with faculty becoming more comfortable with using Zoom, has allowed us to reach more faculty more effectively.

Rebecca: One of the things that I saw so powerful this January, in our experience on our campus, was all of the faculty who volunteered to do sessions and talk about their experiences and support other faculty experimenting with things. And I think it was just this jolt that caused us all to have to try something new, that was really, really powerful. We all get stuck. Even those of us that know evidence-based techniques, we get stuck in our routines, and sometimes just allow inertia to move us forward and replicate what we’ve done before because it’s easier, it saves time, and we have a lot on our plates. And it’s really about being efficient, because we just have too much to do. So it was nice, in a weird way, to have that jolt to try some new things. I heard some great things from faculty that I’ve never heard from before I learned some things from some other faculty. And it was really exciting. And the personal place in my heart that I get most excited about, of course, is how many faculty got really excited about things related to inclusive pedagogy, and equity, and accessibility. We offered, on our campus a 10-day accessibility challenge that we opened up to faculty, staff, and students as part of our winter conference sessions. And we had record accessibility attendance… never seen so many people interested in accessibility before. But that came out of the experience of the spring and the fall, and people really seeing equity issues and experiencing it with their students. They witnessed it in a way that it was easy to ignore previously. And so I think that faculty, throughout this whole time, have cared about the experience that students have and want students to have equity. They just didn’t realize the disparity that existed amongst our students. And the students saw the disparity that existed amongst students, which was a really powerful moment, really disturbing for some students who had to share that moment with other people, but also a really useful experience for faculty to really buy into some of these practices about building community, about making sure their materials were accessible. And all of that has resulted in a much higher quality education for our students.

John: It was really easy for faculty to ignore a lot of these inequities before, because the computer labs, the Wi Fi, the food services, and library services, and lending of equipment provided by institutions, compensated for a lot of those issues, so that disparities in income and wealth were somewhat hidden in the classroom. But once people moved home, many of those supports disappeared, despite the best efforts of campuses in providing students with WiFi access with hotspots or providing them with loaner computers. And those issues just became so much more visible. It’s going to be very hard for faculty to ignore those issues, I think, in the future, because it has impacted our ability to reach a lot of our students. And it has affected the ability of many of our students to fully participate in a remote environment. But going back to that point about people sharing, I also was really amazed by how willing people were to volunteer and share what they’ve learned in their experiences. Typically, when we put our January workshop schedule together, we call for workshop proposals from people. And we typically get 5 to 12 of those, and they’re often from our technical support people on campus. And it’s rare that we get faculty to volunteer. And normally we have to spend a few months getting faculty to volunteer so that we get maybe 20 or 30 faculty to talk about their experiences. We had about 50 people just volunteer without anything other than an initial request, and then a few more with a little nudging, so that we ended up with 107 workshops that were all very well attended. And there were some really great discussions there because, as you said, people were put in an environment where the old ways of doing things just didn’t work anymore, and it opened people up to change. We’ve been encouraging active learning and we’ve been encouraging changes in teaching practices. But this pretty much has reached just about everybody this time in ways that it would have been really difficult to reach all of our faculty before.

Rebecca: It’s easy during a time like a pandemic to just feel like the world’s tumbling down. And there’s no doubt about that. But it’s a time where I’ve also been really grateful to have such great colleagues. Because not only have we seen faculty supporting each other and using new technology, the advocacy that they’ve demonstrated on behalf of students who really had needs has been incredible. Likewise, for faculty, we’ve witnessed some really interesting conversations amongst faculty about ways to reduce their own repetitive stress injuries and other accessibility issues that faculty are also experiencing, equity issues that faculty are experiencing, caregiving responsibilities that are making things really challenging for faculty. But there’s a really strong network of support amongst each other to help everyone through and there’s no word to describe what that means other than being grateful for it, because people have been so supportive of each other. And that, to me, is pretty amazing.

John: Faculty have often existed in the silos of their departments. But this transition has broken down those silos. It’s built a sense of community in a lot of ways that we generally didn’t see extending as far beyond the department borders. There were always a lot of people who supported each other, but the extent to that is so much greater.

Rebecca: So we’ve been talking a lot about this faculty support. John, can you give a couple of examples of things that faculty have shared that have worked really well in their classes that they weren’t doing before?

John: One of the things that more and more faculty have been doing is introducing active learning activities and more group activities within their classes in either a synchronous or asynchronous environment. And that’s something that’s really helpful. And as we’ve encouraged faculty to move away from high-stakes assessment, and many faculty have worked much more carefully about scaffolding their assignments, so that large projects are broken up into smaller chunks that are more manageable, and students are getting more feedback regularly. Faculty, in general, I think, have been providing students with more support, because when in a classroom, you were just expecting students to ask any questions about something they didn’t understand. And sometimes they did and sometimes they didn’t. But I think faculty realize that in a remote environment, all those instructions have to be there for students. So in general, I think faculty are providing students with more support, more detailed instructions, and often creating videos to help explain some of the more challenging parts that they might normally have expected students to ask about during a face-to-face class meeting.

Rebecca: I think previously, although faculty want to be supportive, they may not have been aware of some of the mental and emotional health challenges that students face generally, but have been amplified during the pandemic. Students who might experience anxiety or depression and how that impacts their ability to focus, their ability to organize themselves and organize their time, all of those things have become much more visible, just like those equity issues. And so I think that faculty are becoming more aware of that emotional piece of education and making sure that people feel supported so that they can be successful. And even just that kind of warm language piece of it, and being welcoming, and just indicating, like, “Hey, how are you doing? I really do care about what’s going on with you.” And having those chit chat moments sometimes even in a synchronous online class, open up that discussion and help students feel like they’re part of the community and really help address some of those issues that students are facing.

John: And I think a lot of the discussion is how can we build this class community when we move away from a physical classroom. So there have been many discussions, and many productive discussions, on ways of building this class community and helping to maintain instructor presence in asynchronous classes, as well as helping to maintain human connections when we’re all distanced, somehow.

Rebecca: I think that also points out the nature of some of our in-person classes and the assumptions that we made, that there were human connections being made in class when maybe they weren’t, or maybe there wasn’t really a community being built, because students may also not know each other there. So I think some of the lessons of feeling isolated maybe themselves, or seeing their students feel isolated, has led faculty to develop and take the time to do more community-building activities. So that there is that support network in place sp that students are able to learn, the more supported they feel, the more confident they feel, the more willing or open they’re going to be to learning and having that growth mindset.

John: And we’re hoping that all these new skills that faculty have acquired, will transition very nicely when we move to a more traditional face-to-face environment in the fall.

Rebecca: …or sometime ever… [LAUGHTER]

John: At some point, yes. [LAUGHTER] But one thing we probably should talk about is something I know we both have experienced is the impact on faculty workloads.

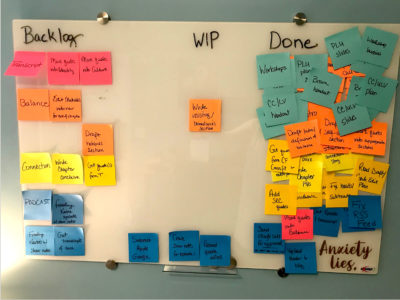

Rebecca: It’s maybe grown just a little, John, I don’t know about you, but there’s some of it that has to do with just working in a different modality than you’re used to. So there’s some startup costs of just learning new techniques. Then there’s also the implementation of using certain kinds of technology that are a little more time consuming to set up than in person. So, the example I was giving to someone the other day was, I might do a whiteboard activity in person that requires me to grab some markers and some sticky notes. That’s my setup. But in an online environment, I need to have that organized and have designated areas for small groups. And I need to have prompts put up. And there’s a lot of structural things that need to be in place for that same activity to happen online, it can happen very seamlessly online, but there’s some time required to set it up. So there’s that. We’ve also all learned how low-stakes is so great, and how scaffolding is so great, but now there’s more grading. And somehow, I think there’s more meetings.

John: Yes, but in terms of that scaffolding, we’re assessing student work more regularly, we’re providing them with more feedback. And also going back to the issue of support materials, many of us are creating new videos. And when I first started teaching, it was very much the norm for people to lecture. And basically, my preparation was going into the cabinet and grabbing a couple of pieces of chalk and going down to the classroom and just discussing the topic, trying to keep it interactive by asking students questions, giving them problems on the board, having them work on them in groups. But I didn’t have to spend a lot of time creating graphs with all the images on my computer. I didn’t have to create these detailed videos and these transcripts and so forth, that I’d share with all my students now. And there’s a lot of fixed costs of moving to this environment, however, we’re doing it. That has taken its toll, I think, on all of us, as well as the emotional stress that we’re all going through during a pandemic.

Rebecca: I know one of the things that I’m concerned about is the ongoing expectation of time commitments that are not sustainable… period.

John: It’s one thing to deal with this during an emergency crisis. But this has been a really long emergency crisis.

Rebecca: And I think we’ve all seen the gains that students have had or felt like it’s worth the time and effort to support students. But it’s also time to think about how to support faculty and staff who have been doing all of that supporting and we need a reprieve… like, winter break wasn’t a break, summer break wasn’t a break, there isn’t a spring break, wellness days weren’t a break. Everybody just needs a vacation.

John: Yeah, I feel like I haven’t had a day off now since the middle of March of 2020.

Rebecca: I think one of the next things we need to be thinking about is: we created a lot of things that we could probably recycle and reuse in our classes, and so there were some costs over the course of the year. But perhaps they’re not costs in the future because we’ve learned some things. There may also be some strategizing that we need to do about when we give feedback or how detailed that feedback is with these scaffolded and smaller assignments so that we can be more efficient with grading. We’ve talked in the past on the podcast about specifications grading and some other strategies and ungrading. So maybe it’s time to think a little more or more deeply about some of these things now that we have them in place. How can we be more efficient with our time and work together to brainstorm ways to save ourselves time and effort and energy and still provide a really good learning environment?

John: Specifications grading is one way of doing it. But having students provide more peer feedback to each other is another really effective way of doing that. We’ve talked about that in several past podcasts, but that is one way of helping to leverage some of that feedback in a way that also enhances student learning. So it’s not just shifting the burden of assessing work to students, it’s actually providing them with really rich learning opportunities that tend to deepen their learning.

Rebecca: I know one strategy that I’ve implemented this semester, that definitely has saved time, although I just need to get more comfortable with my setup, but just I need to practice it, is doing light grading and the idea of having a shortlist of criteria. And then that criteria is either met, its approached or it doesn’t meet. And it’s a simple check box. And essentially, the basic rubric is what it looks like to meet it. And either you’ve met it or you haven’t. And that’s a much more efficient way of…

John:…either you’ve met it, you’ve almost met it, or you haven’t…

Rebecca: Yeah. And so that’s worked pretty well for me this semester. And I think it’s helping me be a little more efficient. And then I say like, “Okay, and ‘A’ is if you have met all of the criteria, ‘B’ is if you’ve met a certain percentage of the criteria, and approach the rest,” that kind of thing. The biggest thing for me is just getting used to my new rubrics and not having to like “Wait, what was that again?” when you go to grade it. But, I think, with practice, next time I go to use them, it’s gonna be a lot faster.

John: Going back to the point you made before, a lot of people have developed a whole series of videos that can be used to support their classes. Those can be used to support a flipped face-to-face class just as nicely as they do in a synchronous course, or a remote synchronous course. So a lot of the materials that faculty have developed, I think, while it won’t lighten the workload of faculty, can provide more support for students in the future without increasing f aculty workload as much as it has, during the sudden transition when people are switching all their classes at once to this new environment we’re facing. I know in the past, when I’ve normally done a major revision of my class, it’s normally one class that I’m doing a major revision on. And then the others will get major revisions at a later semester or a year. But when you try to dramatically change your instruction in all of your classes at once, it’s a tremendous amount of work.

Rebecca: I think another place where we’ve seen a lot of workload increase is also an advisement. There’s a lot of students that are struggling, many more students have questions about what to do if they’re close to failing, whether or not they could withdraw. what it means to leave school or come back to school, we’ve had the pass/fail option. So that raises a lot of questions. There’s a lot of those conversations that certainly we have, but they’re just more of them right now. And I would hope that as the pandemic eventually goes away, then some of that additional advisement will also start to fade away as well. We’re just drained. We imagine that you’re all drained too.

John: We always end these podcasts with the question, “What’s next?”

Rebecca: God, I hope there’s a vacation involved. Our household is dreaming about places we can go, even if it’s just to a different town nearby, as things start to lighten up, just to feel like we’re doing something… anything.

John: The vaccines look promising, and the rollout is accelerating. And we’re hoping that continues. And let’s hope that a year from now we can talk about all the things we’ve learned that has improved our instruction in a more traditional face-to-face environment.

Rebecca: The last thing I want to say is I hope everyone has, at some point, a restful moment in the summer, and we find the next academic year a little more revitalizing.

John: I think we could all use a restful and revitalizing summer to come back refreshed and energized for the fall semester.

[MUSIC]

John: If you’ve enjoyed this podcast, please subscribe and leave a review on iTunes or your favorite podcast service. To continue the conversation, join us on our Tea for Teaching Facebook page.

Rebecca: You can find show notes, transcripts and other materials on teaforteaching.com. Music by Michael Gary Brewer.

[MUSIC]

178. Teaching for Learning

As we again begin planning for the uncertainties of the fall semester, it is helpful to have a rich toolkit of evidence-based teaching practices that can work in multiple modalities. In this episode, Claire Howell Major, Michael S. Harris, and Todd Zakrajsek join us to discuss a variety of these practices that can be effectively matched with your course learning objectives.

Claire is a Professor of Higher Education Administration at the University of Alabama. Michael is a Professor of Higher Education and Director of the Center for Teaching Excellence at Southern Methodist university. Todd is an Associate Research Professor and Associate Director of Fellowship Programs in the Department of Family Medicine at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Claire, Michael, and Todd are the authors of many superb books and articles on teaching and learning in higher education. In June, they are releasing a second edition of Teaching for Learning: 101 Intentionally Designed Educational Activities to Put Students on the Path to Success.

Show Notes

- Major, C. H., Harris, M. S., & Zakrajsek, T. (2021). Teaching for learning: 101 Intentionally Designed Educational Activities to Put Students on the Path to Success. Routledge.

- Cacoo

- WordClouds

- AnswerGarden

- Padlet

- Kahoot!

- Formative

- Google Jamboard

- Kelly, K., & Zakrajsek, T. D. (2020). Advancing Online Teaching: Creating Equity-Based Digital Learning Environments. Stylus Publishing, LLC.

- Kevin Kelly and Todd Zakrajsek (2021). 172. Advancing Online Learning. Tea for Teaching. January 27.

- POD Network

- Lilly Conferences

Transcript

John: As we again begin planning for the uncertainties of the fall semester, it is helpful to have a rich toolkit of evidence-based teaching practices that can work in multiple modalities. In this episode, we discuss a variety of these practices that can be effectively matched with your course learning objectives.

[MUSIC]

John: Thanks for joining us for Tea for Teaching, an informal discussion of innovative and effective practices in teaching and learning.

Rebecca: This podcast series is hosted by John Kane, an economist…

John: …and Rebecca Mushtare, a graphic designer.

Rebecca: Together, we run the Center for Excellence in Learning and Teaching at the State University of New York at Oswego.

[MUSIC]

Rebecca: Our guests today are Claire Howell Major, Michael S. Harris, and Todd Zakrajsek. Claire is a Professor of Higher Education Administration at the University of Alabama. Michael is a Professor of Higher Education and Director of the Center for Teaching Excellence at Southern Methodist university. Todd is an Associate Research Professor and Associate Director of Fellowship Programs in the Department of Family Medicine at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Claire, Michael, and Todd are the authors of many superb books and articles on teaching and learning in higher education.

Rebecca: Welcome, Claire and Michael and welcome back, Todd.

Todd: Thank you, Rebecca.

Michael: Good to be here.

John: Thanks for joining us. Today’s teas are:

Todd: I got myself a nice hibiscus tea, in my favorite little mug.

Rebecca: Awesome.

Michael: And I have a nice regular Co’ Cola.

Claire: Chocolate milk, signing in here. [LAUGHTER]

Rebecca: I think that might be a podcast first, Claire. [LAUGHTER]

Claire: I’m 12, basically. [LAUGHTER]

Rebecca: I’m drinking Scottish afternoon.

John: And I’m drinking ginger peach green tea. We’ve invited here today to discuss the forthcoming second edition of Teaching for Learning: 101 Intentionally Designed Educational Activities to Put Students on the Path to Success, which forms a nice acronym of IDEAS. The first edition provided faculty with a large variety of evidence-based learning activities that faculty can adopt to enhance student learning. These were grouped into eight categories of teaching approaches, lecture, discussion, reciprocal peer teaching, academic games, reading strategies, writing to learn, graphic organizers, and metacognitive reflection. What will be new in the second edition?

Michael: Thanks, John, for the overview and also for having us here today to talk about this. We’re very excited about the second edition. I think we’ve got a great team here, I so enjoy working with Todd and Michael on it. Basically, we’ve kept the same structure that you mentioned before, we have the same eight categories. We have the same structure within each chapter where we move from research to practical tips and specific ideas that people can use in their own classes. The idea is that it is a very broad kind of technique that we include when we include the techniques and when we talk about the research. So it is something that people from all disciplines and fields could in theory use for their own classes. Now, in practice, people have to make decisions about what will work best for their learners at their institutions and their disciplines and fields. So that part has stayed the same. We have updated the research from the first edition to the second. So it’s five years later. So we have included many new research studies to support the message and what the research shows us about what works well in higher education, what has been shown to change educational outcomes of learners, what can faculty do in particular that will help student learning. Another thing that is new in this edition, and I think this is really timely right now, is a focus on online learning. So in the first edition, we talked a lot about how these would work in in-class or onsite settings. In this edition, we go that next step and say, “Here’s some of the theory about what it means to do this online and here are some techniques.” And then within each specific idea, we say specifically, here are some tools that you can use to implement this in an online environment. So we have spent a lot of time working through that. We know how many people have shifted from onsite to online or hybrid courses and how important this is for successful teaching right now. So there’s a big focus on that.

Michael: One of the things as we were going through working on the online elements of this. that’s only become that much more important in light of the pandemic, is understanding the ways to blend the in-person technique and technology together. And that’s something, I think, as we’ve certainly gone through the last year everyone has done that in a much more detailed way. But I think what we’ve in part set out to do here, because we started working on this before the pandemic, is there elements of technology and teaching that faculty should be including afterwards after the pandemic is over? …And so one of the things I think readers will be able to take away. This is not a book written in response to the pandemic… that we can take these various techniques, take technology, take the understanding of your learners and context, as Claire mentioned, and then together figure out what is the best activity in your setting. Think that’s, as we set out identifying the various techniques throughout the book, is understanding that no class, no instructor is going to be comfortable with everything. So we’ve tried to give what I like to think of as a broad menu for faculty under each of the broad topics but also in terms of individual strategies and techniques that faculty can use in their setting. And the hope is, if you need an idea to use in your class that day, you can pick this book off the shelf, and somewhere in there, it’s going to be something that’s gonna work.

Rebecca: I think we really love the mix of both the research and the practical aspects of the book. I think sometimes either it’s just practical, or it’s just the research, and it’s hard to bring them together. So having everything in one place is very handy. [LAUGHTER] Faculty like that. We like convenience for sure. One of the things that I’ve been doing some research on recently is some students complaining about this online environment being so text heavy. And so I’m kind of curious if you could talk a little bit about maybe some of the research on graphic organizers and some of the strategies because that’s a visual way of handling some information in a time where students are feeling really bogged down by text.

Michael: I think to your first point, this is critically important. As we first started talking about this book in the very, very early days, one of the things we wanted to do was to bring together both the research literature, what do we know from the scholarship, but also what are the practical things that faculty need to know how to implement these ideas. And so we very much kept that. That DNA was part of our very early conversations, and is still part of the second edition. And I think one of the things that we found in terms of writing the book, and I think, as we’ve heard from folks who’ve read it, subsequently, is to be able to have access to the research for faculty, those of us who are in teaching centers, and faculty developers, we live this stuff every day, we know where the research is, and what the most recent findings are. For most faculty, whether at an institution focused on teaching, or even researchers, that access is much more difficult to find, right? It’s spread out in hundreds of journals, most of which just folks in the disciplines don’t necessarily read. And so trying to bring that out, and also insights from related disciplines. This is very difficult to access all this literature, because it’s spread out in so many different outlets, it’s in books, it’s in journals, it’s in places like podcasts, there’s all these places to get the information. It’s really difficult, I think, for a faculty member with a limited amount of time to dedicate to course planning and preparation to find all these resources. So that’s what we wanted to do was bring that together, but also remembering that faculty need to be able to take all that information, I think it’s all of us have worked with faculty, we found that they want to know that it’s researched-based, and what those research findings are, but then they want to quickly get to: “Now, what do I do with this information?” And so that’s the way we’ve set up the book is we’re going to go through the literature, if you want to do a deep dive there, all of that information is there. But then we also want to be able to provide some really tangible tactical things for a faculty member to do. And so as we designed all the ideas and thought about the updated literature, that’s still the core tenet of what we want to do.

Todd: Next. I think the second part of the question,you said, Rebecca, was the visual aspects, specifically. So, I thought Michael covered it really, really well. But there’s a whole section in the book with graphics, of course, and just so many different ways you can use the tools that are out there: concept mapping right now, and doing word clouds, and setting up different ways for people to share a space and to drop in photos and images. And there’s a lot of them in there. And I like what Michael said in terms of there’s so much information, it becomes really overwhelming. So my educational technology list is 118 different educational solutions right now that are being used. And so what we try to do in the book was spread out not all 118 of them, but we spread them out. So if you’re interested in concept mapping, here’s a program called Cacoo. And if you want to do word clouds, there’s the traditional WordClouds. But there’s also AnswerGarden, which gives you a little bit more opportunity to put some text in there. But. lots of things on graphics.

John: Going back to that division of teaching and research and practical tips . The research is not just on the general principle of how these things work, but specific studies of how the individual tools or the individual approaches have been used, and that I found really helpful. In the new addition, is this most appropriate for people teaching synchronous courses, or you mentioned that there’s the addition of online components, are the online components primarily asynchronous online, or synchronous online, or some combination of those.

Todd: Actually, that’s great, because this was a really exciting project to do. And one of the things we did to update the book was we went in, and actually, there’s not 101. The title of the book is 101 Intentionally Designed Activities. I would challenge anybody who wants to sit down and rattle off 101, I want to hear you do it. Because when Claire and Michael and I got together we did, we said yeah, 101 sounds great. And we got up to 100. And then everything started to sound like a variation on something we’ve already done. So the hundred and first one is actually a do it yourself intentional. Isn’t that great?

Rebecca: It’s perfect.

Todd: Take your information and apply it. And the reason I bring this up is that means there are 100 in there, 100 different suggestions we have of how to engage your students. For this second edition we went through and we came up with one synchronous and one asynchronous way of doing each one of those. So this book actually has 200 different ways to engage your students in synchronous and asynchronous classes. And I got to tell you that I was really impressed with the team here. To be able to pull that off is really, really challenging. Some of them are very easy. If you want to basically do a small group discussion or post something, you use Padlet or something is really easy. Some of them became really interesting. So for instance, Kahoot! is a great adaptation to something like a Jeopardy type of thing. But then how do you do something like Jeopardy in an asynchronous course, where it’s going across time? So we’re digging through and Kahoot! It turns out has a way of doing that. So, really excited about having different ways of doing this in both synchronous and asynchronous class.

Claire: John, you mentioned how much research there is about the individual techniques. And I just want to share that there is so much research being done in education right now. It’s just blossomed as a field of study, and that’s wonderful. But I think Michael alluded to the fact that faculty members don’t have time to sit down and read 1000 studies, but we do, right? We did. And so we’re sharing that information. We’ve synthesized and collated and culled out what didn’t look like such a good study, or trying to make it into something that’s accessible for faculty who are busy and may not want to read that much educational research… I don’t know, hypothetically. So we are trying to say, “Okay, here’s what it says,” and then definitely apply it to practice. You also mentioned the distinction between onsite and online. I think that distinction is becoming a little more blurred than it used to be. When I teach an onsite class anymore, I’m still having my learning management system set up, there’s still stuff that I’m doing through the learning management system, there’s still stuff I’m doing online. When I teach online, I still have, maybe not face-to-face meetings, but I have Zoom meetings, I have these synchronous ones. And it just is not such a hard and fast distinction, I think. It’s like “I do this with people in the room in real time, or I do this through the technology.” And I think we can use things in all kinds of settings, and that’s what we’ve tried to share a little bit. And I do want to give a shout out, or a special credit to Todd on this. Because there are some things that, like he said, just one technique, how would you do it on every one? I’m like, “Oh, well, that’s an assignment, you submit that through your LMS.” And Todd’s like, “No, here’s 47 different other ways you can do that.” [LAUGHTER] And it’s like, there are some really creative ideas, I think, in there about different tools that you can use to do things in different ways. And so it’s not all just submitted as an assignment through your LMS. There are a lot of really cool tools out there, and to go back to Rebecca’s point, can make things more visual and more creative. And I think that involves students in ways that producing more text may not. It’s like “Oh, wow, I get to make this beautiful, professional looking product and share that with others.” And that causes or at least creates an opportunity for engagement in ways that others can’t. So yeah, we tried to share some good ideas about how to use technology. And that technology might be in an online class, or it might be in a hybrid or hyflex class, or it might be in an onsite class where you use technology in a way that supports onsite learning.

Rebecca: I really need to know what strategies were the most difficult to come up with across platforms or cross modalities. I must know. [LAUGHTER] You have to share.

Todd: There was one that took me about four days to get to and so here’s one for you. One of our onsite ones that we did was Pictionary, you know, drawing. So you divide your class into two teams, and somebody takes a marker and starts to draw. And then of course, everyone has to yell out an answer. Do that in an asynchronous class, that becomes challenging. But I stumbled across a program… actually, I shouldn’t say stumbled across, I’ve used it a couple times. But as I was thinking about this, after a couple days, I was thinking, “No, you got to turn that a little bit.” So there’s a program on there called Formative. And Formative is something that you basically come up with an image that you start and you draw like a circle or something and you present that to the class, And then each class member draws what they see of that, and then you can get feedback on that. And it suddenly occurred to me as instead of having people guessing back and forth real time that way, what you could do is provide the basic image for the class and then say, “Okay, I want everybody to draw something and submit it on this date. And then the first person who can figure out what it is, you basically write in.” And so it’s a way to do kind of Pictionary in an asynchronous way. But that was one of the trickiest ones.

Rebecca: That’s funny that you mentioned that particular thing, Todd, because I’m teaching a class this spring, a new class for me, where I was trying to come up with a way of doing Exquisite Corpse, which is a folded paper drawing, where one person would draw a head and then you try to do the body and then the next person does legs or something… something like that with my class. And I came across an example of having different boxes, essentially in a whiteboard app, for each student. And I’m going to do pet robots. And so everybody draws one part of the robot, the nose, and then you pass it to the next person. And then you say, like, “Oh, draw the head,” or whatever. So it’s a way of doing that. But that took me a good few days to come up with a solution.” [LAUGHTER]

Todd: Yeah, it does.

Michael: Well, I thought I knew a lot about technology. And as Claire said, Todd would pull something out that never ever heard of before or heard of, but I never thought to use it in that way. And I think that was one of those challenges is, anytime you’re writing a book, you don’t want to be obsolete by the time it comes out. And so it’s always tricky with technology, because websites change and services change and the ability to do different things change. But I think what we were able to do in the end was, even though it may reference a particular website or software, the underlying design principle will hold even as we get different technology over time. And I think that was one of the things we struggled with five years ago, because I’m just not sure technology across all 100 ideas was there. But I think now we’re at the place where you could at least have some semblance of how you would do this, even if that particular service was no longer available.

Todd: I really liked that you said that because the one that I’ll have to admit, one of the very first times I did exactly what you’re thinking of here is I love doing gallery walks in classes, the traditional gallery walk. And I’m sure the listeners know, but you set up four or five flip charts, you put students in groups, smaller groups, each groups in front of a flip chart, they respond to a prompt, different prompts for each flip chart, and then you rotate and you keep rotating until you come back essentially to the first one. and I thought about it for a little while and thought this would work out really well on a Jamboard. So you go to Google Jamboard, and you set up five boards and people go through it. But just like Mike was just saying, if Jamboard goes away, alright, let’s do it with Padlet. And if Padlet goes away, alright, we’ll do it with something else. So once you think this is a way through technology to do this, then it becomes actually fairly easy to find other ways to do it.

John: For faculty who are reading this for the first time, and they see now 200 techniques, maybe only 100 of which might apply for their courses, they might be tempted to try a lot of those. Would you recommend that people who are redesigning their courses or restructuring their courses try doing many new things all at once? Or should perhaps they use a more gradual approach?

Claire: I think the answer to that question depends a lot on who the faculty member is. I think some faculty members want to go all in and try a lot of new things. I think some might do well trying one new thing, and seeing how that works, and then trying another use thing. I also think that again, it depends on who your students are, what your discipline is. A lot of our techniques, though, are things that can be done in addition to other things. Like you might lecture for 10 or 15 minutes, and then do a think-pair-share. Or you might do a punctuated lecture where you stop and say “What are you thinking about right now?” …or something like that. So these are ones that can be incorporated into what faculty are already doing for the most part. So I really think it depends on what the faculty member wants to accomplish and what works best for their particular situation.

Michael: I agree with Claire, I think there’s a notion of, depending on how many times you’ve taught the class, for example, there may be a different freedom to innovate in different ways. I think the other part though, is we have to be careful if we talk about teaching innovation in this way, is beginning with the end in mind. Changing something for the sake of changing something is not a good idea to use one of these techniques. The idea is: know what you’re trying to get the students to learn. What is the content you’re trying to get them to learn? And then look for a technique that best gets you there. Certainly, as I talk to faculty, and think about ways they might do something different in class, you’ve got to start at that point, then decide what is the most effective way to get your students there. Now as much as I love all of the ideas in the book, they’re not all going to work in every situation, even if you were game to try them all. And that would probably not be an effective way to teach class. But if you know what you want your students to learn… and then we always preach backwards design, there’s a reason we do that. We start there and get them to “what we want to know” and then figure out what’s the best way to do that. And I think that’s, to me, when I think about using these activities in my own classes and as I talk to other faculty, is if I know what I’m trying to convey, I can then say, “Well, now I need to go look for a game because this might be content that’s a little dry, or I know from the past that students don’t enjoy it as much. So maybe a game would be a good thing to spice it up a little bit.” Or if I know this is really important content, and they need to understand it in a very specific way. Well, now let me look for a lecture activity that I can convey that content. So I think that, if you know what you’re doing, then you can use the book and we’ve got the full menu available to you. But if you don’t know what type of restaurant you’re going to, the menu is going to be gibberish.

Claire: I absolutely agree with that. I do want to follow up with one thing though. I would say for the person who is, and surely nobody’s still doing this, lecturing for 50 minutes without a break. Even if you don’t know why you’re going to stop every 15 minutes to do a short thing, like maybe an interpreted lecture or pause procedure or something like that. Even if you don’t know why, go ahead and do it, [LAUGHTER] because it will help your students learn better is why. That’s the answer. We all know about human attention span and all that good stuff, but also just varying the activity a little bit and giving them something to reset their attention span will be really, really helpful to their long-term learning. So even if you don’t have the perfect learning goal crafted out, if you could just stop every 10 or 15 minutes and give them something to do, something short to reset their attention span and get them back on track, they’re going to be able to listen to you more in that next lecture segment. So I absolutely agree with Michael, the one caveat is just stop every 10 or 15 minutes and do something different.

Todd: I love what you just said there, Claire, but I’m not even sure its attention span. I don’t think it’s attention span. And I mean, that is part of it. But cognitive load.

Claire: Well, that’s part of it, too. Yeah.

Todd: Anytime you’re trying to learn something new, how many times have you start to watch a video, a YouTube clip on how to do a change your carburetor on your lawnmower or whatever, that you have to stop after about three steps and say, “Whoops, wait a minute, what was that stop again? We’re the experts and we start spewing all this information. And I love that Claire said that. And I live by backward design. So, I love that one too. But the one thing we know from all the research, that’s the most clear thing out there is that putting something with a lecture always enhances learning. If you’re only doing the lecturing, and then you put something with it, it always does better. My biggest fight over the last three or four years, the research doesn’t actually really say it’s lecture versus active learning. If you read the research, the titles will say that at times… people argue that all the time. It’s not lecture versus active learning. The research is lecture alone versus lecturing with active learning, and lecturing with active learning kicks butt all the time. So I love that.

Rebecca: There’s a lot of faculty who are now teaching online synchronously, which is, you know, a newer modality that’s not written about quite as much. And John and I’ve been talking about that a bit the past few months on our podcasts.

John: …certainly, since March.

Rebecca: Yeah, I guess it’s coming up on a year. But I know one of the things that faculty are struggling with is ways to do some of these activities and build community online as part of that and get students connecting with their peers. Can you talk about some strategies that might be in your book that we could point faculty to looking into more?